Time for another rap music analysis. Attached below is a song-by-song analysis of 52 songs produced by Dr. Dre between 2000 and 2009. To my knowledge, these are all of the songs he produced in these years; that, according at least to Dre’s discography on wikipedia.org (although a more complete one can be found elsewhere I think.) This time period for a Dre production analysis may strike those in the know as somewhat peculiar. To start with, it is after the release of his seminal album 2001 (which was actually released in 1999 – fun fact.) Then, it is before anything recently that he has supposedly done, such as “Kush”, “I Need A Doctor”, or Kendrick Lamar’s “The Recipe” (listed production credentials be damned.) Furthermore, it leaves out “Straight Outta Compton” (1988), as well as his “Chronic” (1992) and Snoop Dogg’s album “Doggystyle” (1994.) So just where, exactly, were these songs released?

To start, it covers the beginning of Em’s work in the new millennium, starting with 4 songs from his “Marshall Mathers LP.” It also covers 50 Cent’s come up on Em’s Shady label (with 5 songs found on that album), as well as Busta Rhyme’s short time on Dre’s Aftermath album, along with Raekwon (2 songs) and Eve (4 songs). It covers some work with the 50 Cent’s G-Unit then (2 songs), as well as Game’s come up on that label before he left for another label. It includes one song by Mary J. Blige, and 50 Cent has the most songs in this period. Unfortunately, this period also covers some of Dre’s darker days quality-wise: 50 Cent’s “Curtis” and “Before I Self Destruct album”, and Eminem’s initial comeback on “Relapse: Refill” (If you’re a fan of Eminem, then you’ll probably definitely want to check out another article I wrote all about his flow on the 2002 song “Business,” which you can read by clicking here.) This period thus interestingly covers both much of his oeuvre that is often criminally overlooked in favor of more popular and critically acclaimed album’s (Doggystyle, Chronic, Straight Outta Compton, 2001), as well as some of his “worst” — worst, for Dre, is relative here, as anything considered half-bad for Dre would be great for other producers. This will all allow us to understand and trace the paths he took after the game-changing “2001” album, as well as how he developed the ideas he had on that album afterwards. Additionally, it will let us see where Dr. Dre may have lost his way a bit towards the end of the first decade of the new millennium, and what we can expect from “Detox.” (Now, if you want to hear a rapper killing it over a Dr. Dre beat, instead of a Dr. Dre production analysis, then check out on my article on Nas’ verse from the 2006 Busta Rhymes song “Don’t Get Carried Away,” available here.) Now, for the orchestration analysis…

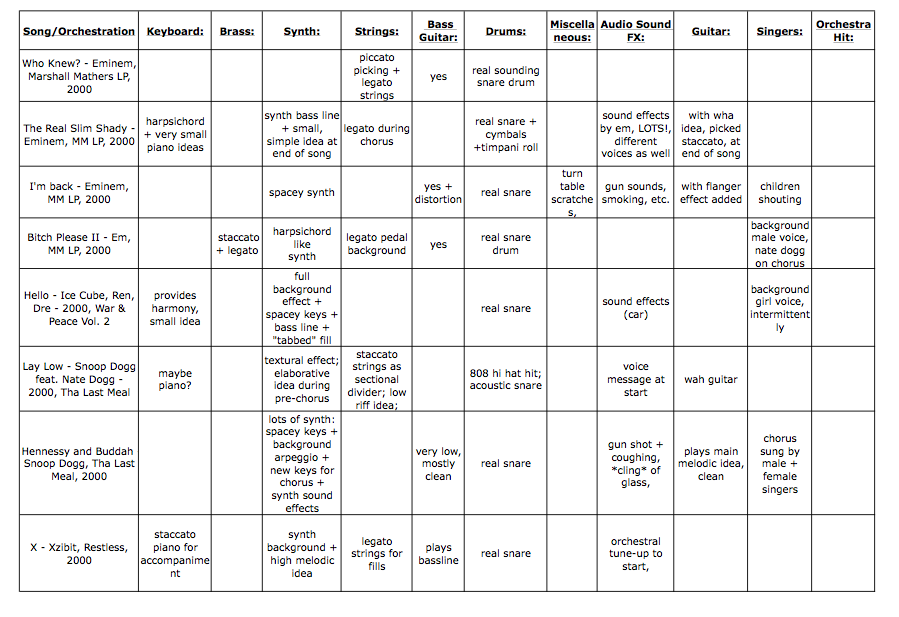

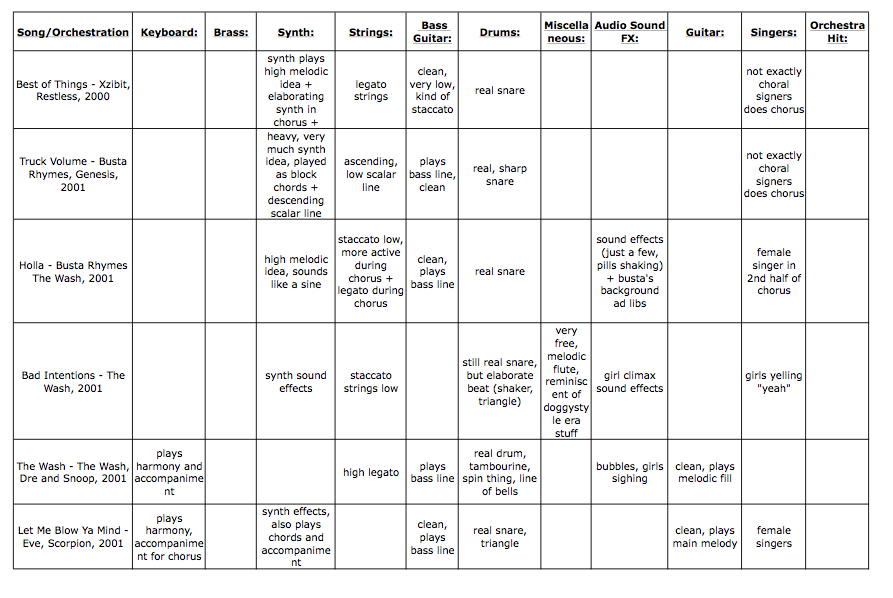

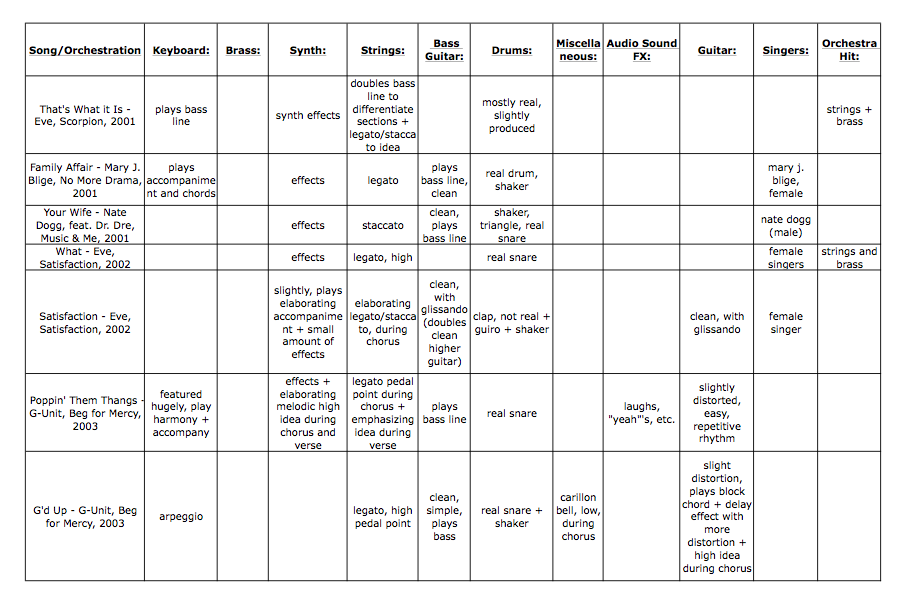

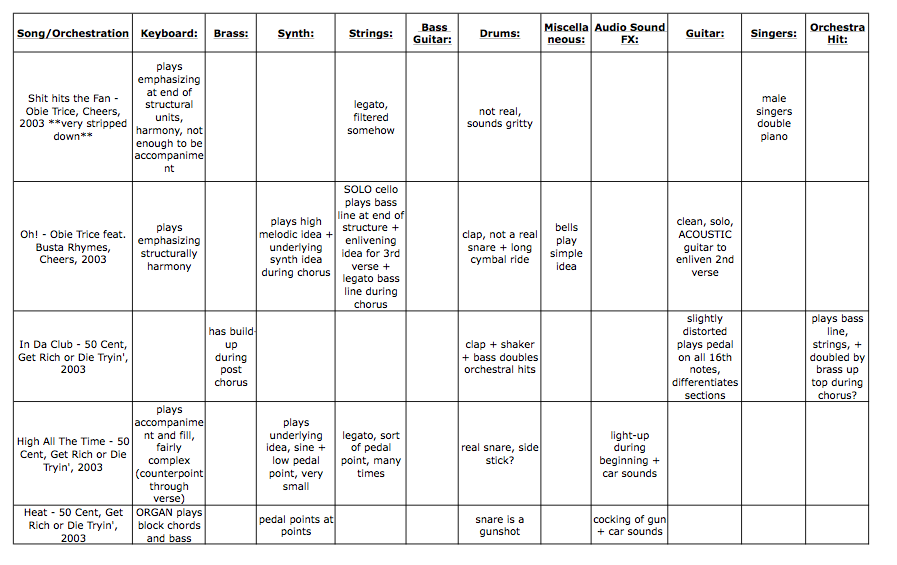

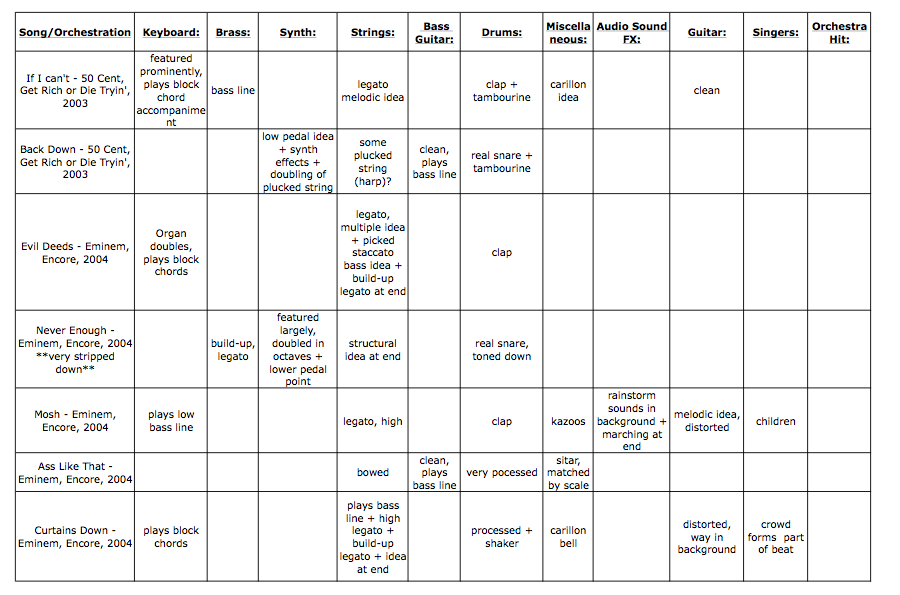

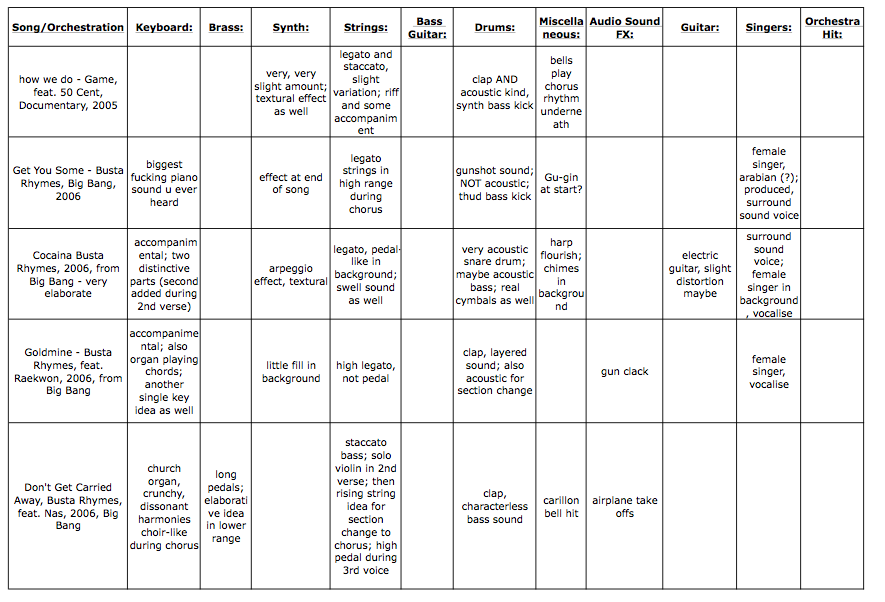

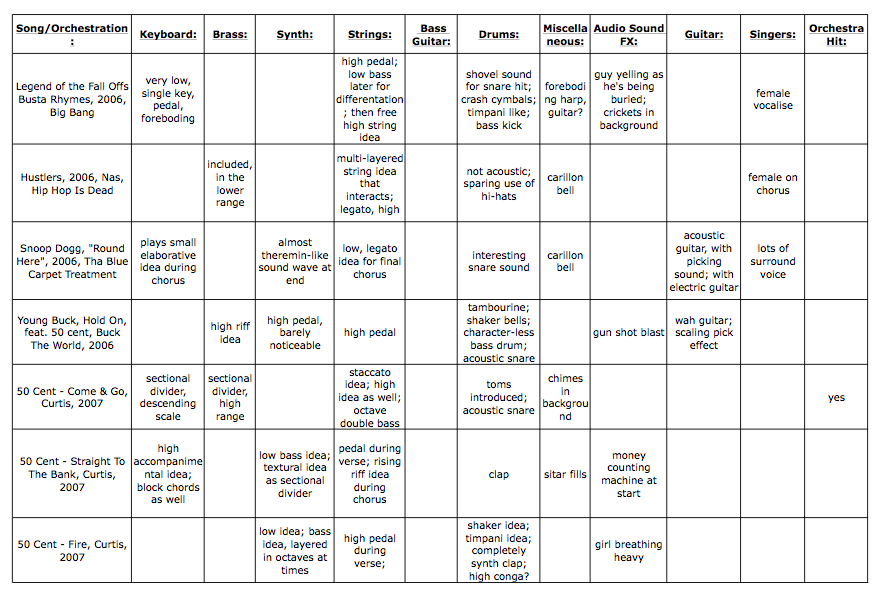

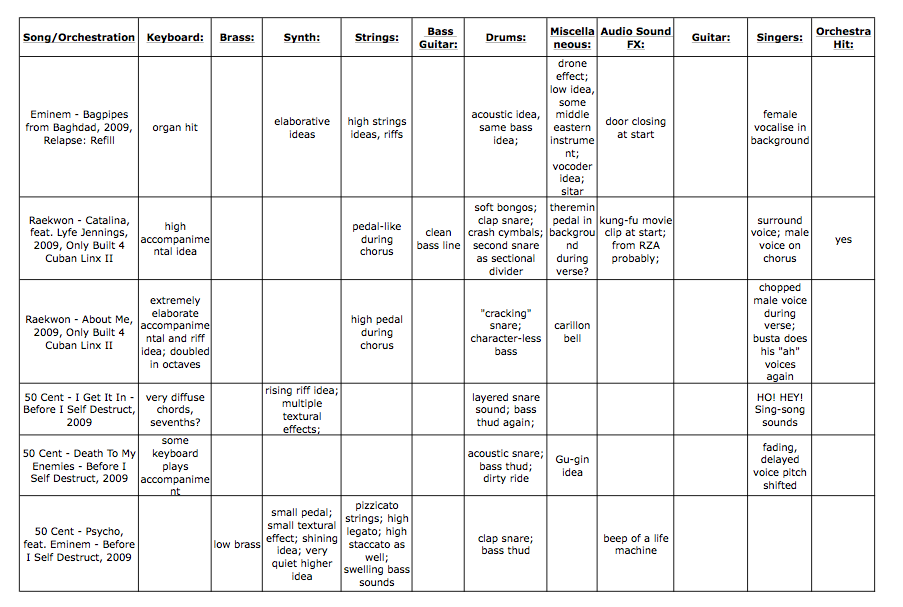

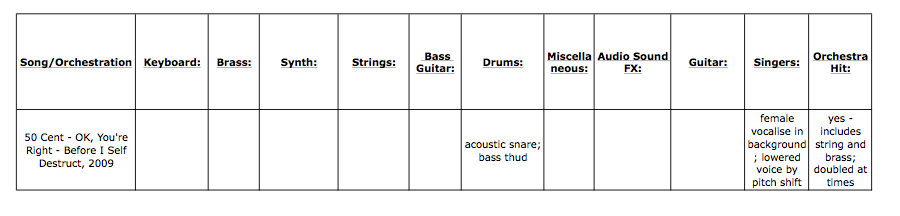

For our purposes here, “orchestration” will basically mean the instrument Dre has chosen to play the musical ideas in his song. Attached below are my notes on all 52 songs, between 2000 and 2009:

All the way on the left is listed the song, the artist, the album the song came from, any guest appearances on the song, as well as the year it was released (it goes in chronological order starting from 2000.) Then, I marked under a couple different categories the musical instrumentation that the song contained: there are categories for keyboard (which includes piano, harpsichord, and organ), strings (cellos, violins,) bass guitar (clean, distorted, etc.), drums (snares, bass kicks, the nature of cymbals or hi-hats, and all other percussion instruments), miscellaneous (instruments that don’t fall under any of the other category), Audio Sound FX (recorded sounds of real-world sounds played during the song, guitar (clean, distorted, wah, etc.), singers (female, male, vocalize, words,) and orchestral hit (which is a big staccato noise by what sounds like a full orchestra,) and general notes all the way on the right. I took notes of varying detail within each cell.

Now would be a good time to mention my Kickstarter campaign, where you can donate so I can publish a book to keep bringing you rap analysis like this one. My work is always to increase the appreciation of music for the average listener, and this book will help me do that.

As mentioned before, this time period covers an extremely interesting cross section of Dre’s work. You have the all-time classics (“The Real Slim Shady,” “In Da Club”, “How We Do”), the absolute bombs – and not the good kind (“Bagpipes from Baghdad,” “Fire”), and the criminally overlooked (“Oh!”, “Get You Some”, “Don’t Get Carried Away” – but this will be addressed in-depth in my “10 Greatest Dr. Dre Songs of All Time Production-Wise” post.) You can go through all of the songs individually, but I will draw some general conclusions.

The most glaring difference between Dre’s output over his entire career, not just this period, and every other popular producer, is that Dre’s output is noticeably free of any soul samples. In direct contradistinction to artistic trends championed by RZA in his work with Wu-Tang and Kanye’s work years later starting with “The College Dropout”, the two most popular producers of the two preceding decades apart from Dre himself, Dre does not sample old soul hits. Soul sampling is found all over in the game today. Instead, we see that he opts to combine “real” instruments (in contrast to synthesized sounds such as synth keyboards) with manipulation of the stereo world (allowing these real world sounds to do things they couldn’t have done in a completely audio acoustic environment, such as phasing back and forth between left and right earphones.) For instance, his favorite instrument seems to be a clean, real-life piano, white and black keys and all. Some kind of keyboard can be found in 75% of his songs (rough estimation of mine without counting.) The nature of this keyboard can differ; sometimes, it plays the accompaniment, giving the song the harmonic underpinning while other riffs and ideas play themselves out above or below (The Wash, 2001). At other times, in a monophonic line it itself plays the riff (Round Here, 2006.) Additionally, not only does he often use the piano, he uses other keyboard type instruments, such as different types of organs (Electric organ – Heat, 2003, or Church organ, Don’t Get Carried Away, 2006.) In what might be the greatest orchestration decision of all time ever made in rap (yes, it’s that good) he sets a harpsichord in Eminem’s “The Real Slim Shady.” The amount of “Fuck You” this communicates to the listener cannot be accurately measured…not that there is an accurate way of measuring “fuck you.” But the harpsichord choice, the most stereotypical, cliché instrument in pop music as representing old, generic pop classical music of some type makes the perfect instrumental counterpoint to Eminem’s message of fuck the world in that song. One can also observe that Dre is not content to play the keyboard simply legato; he also uses it staccato at times, for instance in X, from 2000. He furthermore differs the kind of textures he evokes from the piano. That is, the piano is not always playing block chords. Sometimes it is used in a much more diffuse texture (Cocaina, 2006.) From this, we know that Dre thinks a lot about the color of his orchestration. This can be seen from his use of pedals and octave doublings. Oftentimes, he will have an instrument sustain a single note for a long time (a pedal), or play the same musical idea as another instrument at the same level or in a different octave (doubling.) He does this often with the bass note; for instance, a lot of times when a carillon bell is utilized (the strong minor third upper harmonic of a tuned bell perfectly dovetailing with the minor key sound world Dre wishes to create), such as in Don’t Get Carried Away, 2006, or Hustlers, 2006, it is often doubling a bass note. Furthermore, his use of the piano is often very scaled back, and used in only a superficial manner (without any negative connotation), such as in doubling another musical idea. This reduces the piano to being used only for its timbre, or “sound quality.” Timbre is what allows a person to tell a piano sound apart from a cello sound, even though they are both playing the same note, for example, middle C. Instrumental color is, for our purposes here, synonymous with timbre.

Dre’s treatment of the piano is a sign in general of his treatment of orchestration. No instrument, and no articulation (way of playing an instrument), is off limits for Dre when he steps in the studio to choose instruments. He does what good composers do and makes the instrument do what he wants, not do what the instruments want. He finds ways to utilize instruments in his songs that you’d find nowhere else in natural ways. The following is a short list of rare instruments (in rap music) you’ll find in Dre’s work:

1. Sitar (Ass Like That, 2004, and elsewhere)

2. Carillon Bell (Multiple Times)

3. Flute (Bad Intentions)

4. Kazoos (Mosh, 2004)

5. Gu-gin (finger plucked Chinese instrument – Get You Some, 2006 Death To My Enemies, 2009)

6. Harp (Back Down, 2003, and one other time)

7. Harpsichord (Real Slim Shady, 2000)

8. Some Middle Eastern instrument with a drone (Bagpipes from Baghdad, 2009)

9. Bongos (Catalina, 2009)

10. Acoustic Guitar (Round Here, 2006.)

11. Guiro (Satisfaction, 2002)

12. Theremin (Catalina, 2009)

This calls attention to another distinguishing characteristic of Dre’s post “2001” album sound. He does not use synths as main organizing instruments in his songs, such as by having them play the accompaniment or bass lines (Fire, 2007, for 50 Cent, is definitely an outlier is this regard), but instead uses designed, specific synth sounds more for a textural effect. This can be observed all over; one especially good example is “Hello,” from 2000, written by Ice Cube, feat. Ren, and Dre (for who Eminem ghost-wrote his verse…of course.) Perhaps that is why “Kush”, supposedly the first single from “Detox” (since dropped from the album) sounded so un-Dre-ish to so many people, myself included, and thus was widely disregarded. Additionally, he favors using real, acoustic snare sounds (Best of Things 2000, Truck Volume & Holla, 2001), over any completely synthesized clap sounds, but this started to change towards the end of this 2000-2009 period. His signature bass kick sound is a rather character-less bass “thud”, so lacking of any high frequency sounds that the listener feels rather than hears that it is there (About Me, 2009). Along the same line in drums, Dre favors less complex drum sections (drum sections = bass kick, snares, cymbals, hi-hats, and any other percussion effects.) The emphasis is therefore placed on the melodic instruments (whether they play the melody or not), while the drum sections provides the beat but largely tries to stay out of the melodic instruments’ way.

Audio Sound FX also play a large part in Dre’s production choices. Many of his songs, as can be seen, feature them prominently, especially those with Eminem (Real Slim Shady, 2000.) In fact, he twice uses audio sound FX to supply essential musical information: in Legend of the Fall Offs, 2006, and Heat, 2003, a digging shovel and gun cock sound, respectively, take the place of the snare drum. All over this oevure though, however, Audio Sound FX are featured.

It is important now though to distinguish the different ways in which Dre utilizes his orchestration choices once he has made them. A central technique that gives Dre beats their longevity, the fact that you can listen to them over and over again, is his technique of what I call musical layering. That is, he differentiates structural sections of a song (1st verse from 2nd verse, verse from chorus, outro from intro, etc.,) from each other by assigning unique musical ideas to each one. The epitomic example of this can be found in my analysis of his song “Oh!”. For instance, there, an acoustic guitar arpeggio plays in the background during the 2nd verse, and a solo violin idea plays in the background during the 3rd verse. Then, a contrabass idea appears during the choruses but never during the verses. This makes each section of the song stand out from the others, by making them unique in some way. However, “Oh!” is not an outlier in this regard.

Dre does this everywhere. For instance, in “That’s What it Is”, 2001, Dre doubles the bassline with strings to differentiate sections from each other. He does the same during 2002’s “Satisfaction,” as well as “Poppin’ Them Thangs”, in 2003. This is a major hallmark of Dre’s style. The reader is encouraged to look up different examples on their own on YouTube.

Along with doubling and layering, another hallmark of Dre’s style is his use of the pedal. As explained before, a pedal is when one instrument sustains a note a very long time. Dre’s second favorite instrument, behind the piano, is the string section; it is unimportant which instrument is playing, as they are often very hard to distinguish from each other anyway when they are sampled. Pedals of this type can be found all over: Bitch Please II, 2000, G’d Up, In Da Club, 2003, High All The Time, 2003, to name only a few. These are likewise used to differentiate sections of the song from each other, or re-iterations of the same type of section (verse, chorus) from each other. Dre favors strings so much to the point that they oftentimes completely comprise the musical background for a song; “Who Knew?”, 2000, and Psycho, 2009, are shining examples of this, as Dre uses the three most prominent different articulations for stringed instruments (pizzicato, legato, staccato) all in one song.

Finally, his use of structurally dividing musical ideas is endemic of his style. That is, he will have certain musical ideas play at structurally important places in the song (middle point of verses or choruses, the transition from the end of a chorus to the start of a verse, etc.) to lead from one section of a song to another. These, again, are a hallmark of his style, and so can be found all over, but a good example can be seen in 2000’s “Lay Low”.

Now, before considering the tail end of this period in greater detail, let’s examine some outliers.

“Break Ya Neck”, 2001, not listed, is so different from every other Dre song (due to the prominent featuring of elaborate synth ideas), that I at first questioned whether it was actually ghost produced for Dre (not unheard of in the rap industry today.) However, his other work on Busta’s album “Genesis” is somewhat similar (Truck Volume, Holla), so I overlook it. This speaks to another fact of Dre: he seems to have tried to style himself to fit each new artist he worked with, or at least went through definite, consistent periods of artistic vision. We see that his work with Eve in 2002 is marked by the use of orchestral hits that won’t return until the end of this period. We see that his work with Busta is marked by the prominent use of elaborate synth ideas. Raekwon seems to have received his most elaborate musical treatment on his “Only Built 4 Cuban Linx II” album, starting with the descending piano scale on “About Me.” Then, we see that the carillon shows up at a distinct time in 2006, and remains somewhat constant until 2009. In any event, it may be an interesting idea to look more into, or it may only be what we would expect from a mature artist in his prime.

Another outlier is 2001’s “Bad Intentions.” Although the release date is for 2001 from a movie’s soundtrack, I’m inclined to think that this work dates from much earlier, maybe even mid-90s. The funky flute along with the prominent use of synth and synthesized shaker is simply too similar to his work on “Doggystyle” for me. 2001’s “Your Wife” is similar for me in this regard, although it sounds more similar to “2001” then “Doggystyle.”

We can thus see the direction that Dre took the ideas he initially came up with on “2001.” The move towards real instruments from the prominent synths and 808 drum sounds of “Chronic” and “Doggystyle” on “2001”, which there manifested itself as clean guitars (Still D.R.E.), clean bass lines (Forgot About Dre), and the occasional, heavily processed string part (bass line for Still D.R.E.), continued in a natural evolution to real orchestral instruments, such as real, authentic-sounding strings, pianos, and even harps, sitars, and so on, in this 2000 to 2009 period.

Unfortunately, the next few outliers are not to be seen in a positive light. First, we have 2007’s “Fire”, which so badly tries to imitate 50’s 2003 “In Da Club” and in doing so fails terribly its almost awkward to listen to. From the octave doubling, to the syncopated rhythms of the prominent synth, to the return of the shaker in the percussion, it tries to be “In Da Club” but fails. I can dismiss this with a clean conscience, however, because it was 50 when I’m not sure 50 cared anymore, and it clearly was a club track. If 50 put it down on this track, I’d see it differently.

The outliers came more and more quickly though. “Bagpipes from Baghdad” is certainly unprecedented, even with Dre’s outlandish orchestration choices from before. I reference, of course, the wind Middle Eastern instrument of some type. Again, Eminem completely drops the ball on the rhymes. Even this track wouldn’t be that bad, if Eminem didn’t throw into deep relief just how little musical sense this song makes. To be fair, this is Eminem post-addiction when he was still trying to figure out what the fuck he could talk about. He still could rap musically; he just couldn’t rap poetically. A great example of this is “Drop The Bomb On Em,” from “Relapse,” which I talk about in-depth here.

To be fair, Eminem’s flow on “Drop The Bomb On Em” is sick — it’s just that his words make no goddamn sense. At one point, he even ruins a major storyline of the greatest TV show of all time, “The Wire”, by dropping a major spoiler, without warning. (Don’t look up the lyrics if you plan on watching the show…which you should.)

But Eminem has since figured this out, of course. All you need to see this is look up his track with Royce da 5’9, in their group “Bad Meets Evil”, with Bruno Mars, called “Lighters”. As a sampling:

“I love it when I tell em shove it

Cause it wasn’t that long ago when Marshall sat, flustered, lack lustered

Cause he couldn’t cut mustard, muster up nothing

Brain fuzzy, cause he’s buzzin’, woke up from that buzz

Now you wonder why he does it, how he does it

Wasn’t cause he had buzzards circlin’ around his head

Waiting for him to drop dead, was it?”

Damn. That definitely isn’t the tediousness or monotony of the 23 rappers on the “Most Repetitive Lyricists Ever” list that I compiled and published in another article that you can read here, now, is it?

Things continue to get more and more concerning though. “Death To My Enemies” is in the same category as “Bagpipes from Baghdad”, but this time, the production just isn’t there.

“I Get It In”, however, on deep reflection, might be the most worrisome. The song is largely devoid of the rich variety of musical material that mark the greatest Dre songs (Get You Some, Oh!.) Instead, things are mostly held together by drum sounds, and again, the rapping simply isn’t there. Through this last rash of songs, though, is that there is a complete lack of the musical depth that Dre added to his songs through his techniques of pedals, doubling, structural dividers, interesting orchestration choices, and, most worrying, musical layering. It is like Dre somehow forgot about everything he had learned (and taught us) over a career that is now entering it’s 4th decade. Either that, or he was looking for a way forward, and us mere mortals simply cannot see it.

And so here we are. “Detox” has not been released, and it is fair to guess whether it ever will be at this point. And yes, this is even after taking into account that Dre takes a while with his albums, or as Game puts it so eloquently, “I’m the second dopest Compton nigga you’ll ever hear / the first one only put out albums every 7 years.” I still enjoy listening to 2004’s “Curtains Down” (Eminem) and 2005’s “Higher” (The Game,) when Dre assures us that Detox is “coming.” So what happened?

Well, let’s take a look at the supposed singles for Detox. First, there was “Kush”, then “I Need A Doctor,” and now we have Kendrick Lamar’s “The Recipe” (not a single, but still a recent work.) I swear, on everyone of these songs, Dre was initially listed as the producer, but then after they did not do well popularly, he was switched with someone else. “Kush” is now supposedly produced by DJ Khalil, and mixed by Dre. “I Need a Doctor” says it is produced by Alex da Kid, and mixed by Dre. “The Recipe” is now produced by Scoop Deville, and mixed by Dre.

First off, what the fuck am I gonna be paying money for if Dre isn’t producer? Is he known as the world’s greatest mixer? I don’t think so. There’s a couple things going on here. First, there is my initial conspiracy theory, that Dre changes the credits to keep face. Second, and more likely, that Dre is ghost producing these songs for people. He comes up with the song, gives it to a producer like Alex Da Kid, and releases it under their name to see how it does. Either way, it doesn’t reflect well on Dre’s current state of mind artistically.

It’s safe to say that he’s lost confidence in himself as an artist. The thing is he doesn’t have perspective anymore on just how good he is. We’ve heard it throughout the years: Dre is a perfectionist. The unique pressures and stresses of working with Dre are evident all over his industry relationships, from the number of prominent acts who never released any substantial material on his Aftermath label (Bishop Lamont to start), to the occasional spats that bubble up (such as when 50 threatened to pre-empt their own single’s release by putting the single out by himself.) He just doesn’t realize how good he is, and he just doesn’t realize that, at a certain point, whatever he puts out maybe might not be his 5th classic album, but will be good enough…although I guess that’s what makes Dr. dre Dr. Dre, and what makes us just us.

Honestly, I think he’s got enough material for several albums (several sources corroborate this.) And he was set to release something, but then Kanye’s “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” happened. (I talk about “what happened” in a whole article I wrote entirely about his awesome MBDTF song “Monster,” which you can read here; I also wrote about that album’s extended pop song structures at an article available right here.)

The level that MBDTF raised the bar to is simply incomprehensible. The scope of its musical quality is breathtaking. The sweeping, innovative structural forms , the introspective look into subjects that rap has rarely touched before (“Blame Game”), sweeping, 9 minute opuses like “Runaway” (which Vox Media interviewed me about in one of their videos here,) the deft use of skilled instrumentalists (guitar solo in Devil In A New Dress), the perfect matching of differing style of music (Bon Hiver’s work on the album…) it’s huge. Dre lost his confidence in himself when he saw that.

So what should he do? First off, stop worrying about the fucking headphones. This man is already paid many times over, in all senses of the word. I think he’s distracted himself from what got him in the position to sell headphones with that business enterprise. Second, go back and take a look at his own work. It’s fire man. There’s no doubting it. I can listen to these works over, and over again. Just like every great artistic evolution, he has to build on what he used before. I don’t know why he abandoned his techniques like doubling, pedaling, structural dividers, and musical layering. But it’s what got him there in the first place.

Please Dre. Please release Detox.

Best Regards,

Martin Connor

(You’re biggest fan — is there any doubt about anymore?)

UPDATE — 2/3/2017: Oh, and Dr. Dre? Make sure you do as many songs as possible with Kendrick Lamar. Why? Because of what I say in my articles on Kendrick’s “good kid, m.A.A.d. city” album here, or my “To Pimp A Butterfly” album review here.

Very detailed analysis…thanks keep doing more of these analysis. And some advice I think you should redesign this site, it looks a bit dated but other wise the information is very helpfull.

Thanks for the compliments! They mean a lot. Yeah, I need to re-design the site, it's been something I've been thinking about for awhile. However, I have no idea how to go about doing it, haha. And it's a blogger page so if I'd have to port all my articles manually…I ain't down for that, haha.

Thanks again!

Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Centri Records is a New York based independent record label owned by Rhandy Acosta. It originated as a way for local talent from Queens, NY. Rhoyale’s new single Tonight is now available on Apple Music and Google Play. Add it to your playlist today.

dude this is brilliant! just thought i should pay respect for this work!

Thanks bro! Your compliment really means a lot to me, because I don't make money or anything off this blog, so I really rely a lot on my readers and fans to stay ultra-motivated.

If you want some more articles and secret goodies I keep secret for my biggest readers, hit me up at [email protected]

I've got some more stuff like this on Dre, and others with a classical perspective on orchestration like this one does, so I think you'd like them 🙂

Thanks again bro!

Peace,

Martin

I am a dre fan since 1996 never saw this before.. amazing to know . Great work .

Thanks man! If you hit me up at [email protected] I'd be happy to hook you up with some more shit like this, on instrumentation, and Dr. Dre in particular. In any event, thanks for hitting me up. Peace bro!

Best,

Martin