It’s time for another rap music analysis. However, instead of taking a look at a rapper’s verse, we’ll be taking a look at a producer’s entire song. The song is “Oh!”, off Obie Trice’s album “Cheers”, featuring Busta Rhymes and Dr. Dre on the beat. We’ll be doing harmonic/melodic analysis only insomuch as it furthers our discussion of what I really what to get at here: the proportion/balancing of all the different parts in this song. When one takes a look at how many different musical ideas in the song, and the fact that they are all balanced perfectly together so that the listener’s ear is not overwhelmed but greatly pleased, it is quite amazing. (A couple quick administrative things: I’ve tabbed out the song in its entire form, but I’ll be breaking it down into all of the different musical ideas, of which there are many more than in the typical rap song. I’ve declined to tab out Obie’s verses, as it would’ve taken too long. We’ll look at Busta Rhymes choruses instead, as it’ll be enough for our purposes here. Thus, a stave for vocals is omitted in the sections marked “Verses”, but just imagine one being there. Finally, you can hear the song here. I’ve also included midi recordings of each idea isolated right after the sheet music of them, because posting the entire sheet music for the song would be too much – it’s 16 pages long.)

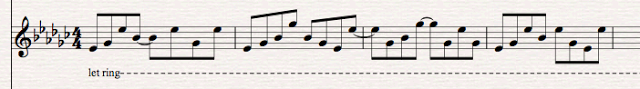

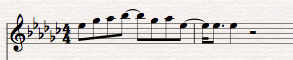

We’ll begin by considering each musical idea separately, starting from the highest idea (in pitch) and then moving down to the bass. Let’s start with this idea:

This idea is in Eb minor, as is the entire song. This melodic idea in the high strings that opens the song outlines the tonic chord (the chord that feels like “home”), by mentioning the Eb, Gb, and Bb, before returning to Eb at the end. It is an interesting idea, with a good amount of melodic (a wide number of different notes that aren’t part of the underlying chord, a smooth up and down contour/shape)_ and rhythmic action (sixteenth note syncopations, and off-beat rhythms.) It is also worth noting that this idea repeats every two bars. Let’s consider the idea just below that one:

Consider how this idea (played by bells) contrasts with the one we just looked at. It’s much simpler: there are only quarter notes occurring right on each beat, and the melodic content is all by stepwise motion (all of the notes are right next to each.) It outlines a 3 – 2 – 1 scale degree motion in Eb minor’s relative major key, Gb. This contrasts with the general Eb feeling of the rest of the ideas. This idea also repeats every 2 bars. I would consider this idea as a mixture of melody (forming the foreground of the music) and the accompaniment (which can be thought of as the background of the music.) This is because it plays only one line at a time, but the idea is not strong enough to stand on its own. We’ll return to how all of these ideas interact together once we’ve gone through all of them.

This piano part provides a large amount of our harmonic information in the song. It is a iv – i motion, Ab minor chord – Eb minor chord, in Eb minor (if that doesn’t mean anything to you, don’t worry about it for now.) This idea likewise repeats every 2 bars. It contrasts with both ideas that precede this one because it is a completely accompanimental idea. It is not in the foreground of the music. So count all of the different instruments used so far: bells, piano, and violin strings. We’re slowly unearthing what makes this song remarkable. Moving along:

This idea, played by a cello, is also strongly rooted in Eb. You can see how the line begins on Eb and ends on Eb. This idea is important because it repeats every 8 bars (imagine that there are 6 blank bars after the last bar in the image above; also note that that last Eb staccato completely alone in the 2nd bar starts the beginning of the new section; the 8 notes in the bar before it are pick-up notes to it.) We’ll return to why exactly this makes the idea important. This also feels like a return to Eb.

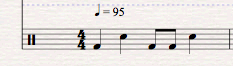

Finally, we reach the drum idea. Note that this drum idea is rather simple. It lacks other elements that might make it more sophisticated, such as hi-hat hits, or a more complex bass kick rhythm. This idea repeats once every bar.

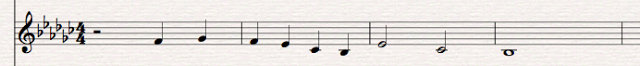

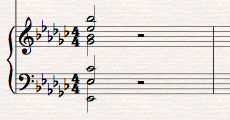

These are the first 5 ideas that are presented in the song. They all start playing together in the first 8 bars of the song, before the Obie Trice verse starts. Let’s see how they are all perfectly balanced with each other, and support the rapper’s rhythms. We’ll consider how all of these ideas when placed together are balanced both vertically and horizontally. When we say they are balanced vertically, we will be considering where each idea falls in the range of pitch, whether they are low in pitch, in the middle in pitch, or high in pitch. Let’s go through in the same order that we first went through them. The idea in the violins is very high. The idea in the bells and the idea in the piano are in the middle. Meanwhile, the cello is in the low part of the range. Note how the ideas are spread out equally across the entire rage. If you were to take the highest and lowest notes of each idea and place them all on the same piano stave, it would look like this:

The range of each idea is beamed together. That is, the two highest notes (Eb to Bb) are the range of the violin strings, the Bb to Gb below that is the bells, the Eb to Cb below that is the piano’s range, and the Eb to Eb below that is the cello staccato idea. You can see that the whole range of pitch is covered, and it is covered in a very spread out and balanced manner. None of the ideas overlap, and none of the ideas are ever more than a perfect fifth interval away from each other. In doing so, the ear can handle so many different ideas at once. They won’t confuse each other because their ranges are spread-out, and different instruments play them. With this many different musical ideas, we can understand why Dre decided to keep the drum pattern simple (I haven’t considered the drums in the range of pitches because the drum and snare sound are of unspecific pitch, while the instruments are all of specific pitches. Thus they can be considered as being in different spheres, at least for our purposes here.) Anything more complex would have overburdened the listener’s ear. Now consider the function of all the ideas together. You have an interesting melodic idea in the high strings; an arpeggio-like idea in the bells below that is less interesting, and half-melodic half-accompaniment; you have the piano idea below that, that is all accompaniment; and then you have a bass line that provides harmonic motion (even it is comparatively simple harmonic motion.) There is a definite hierarchy of which ideas are in the foreground and which are in the background, which ideas are more interesting and which ideas are less interesting. No two ideas, both being very interesting, are competing to be heard over each other. Thus we see another example of Dre’s balancing of the music. Now we can look at how these ideas ultimately support the rapper’s words by looking at the ideas horizontally (that is, the additive effect of their rhythms.)

You can see that none of the ideas are very rhythmically complex. Yes, there are ideas that are more complex and less complex, but they are nothing compared to how complex the rapper’s voice is (we are now considering the interaction of these 5 ideas with the rapper’s words – also a musical idea – in the chorus section.) The rapper’s voice include lots of sixteenth notes, as well as strong syncopation (more in Obie Trice’s verse than Busta’s chorus.) By being on the simpler side generally, these musical ideas clear out horizontal (rhythmic) space for the complexity of the rapper’s words. Once again, we see that no one idea competes with the rapper’s words for the same musical space (just as the 5 ideas considered at first did not compete for the same musical space). In this way the musical ideas let the rapper’s words take forefront, as they should. It focuses the listener’s attention on the lyrics.

Now let’s consider how the different lengths of the musical ideas function structurally in the song. As we’ve noted, the bell idea and the piano idea all repeat every 2 bars, while the drums repeat once every bar. These 3 ideas together are the only ideas constantly heard throughout the whole song. They form the backbone of everything the listeners hears. The high violin idea repeats every 2 bars as well, but it comes and goes; it is not playing constantly. Dre inserts the violin idea and takes it away at structurally important parts in the song: for instance, in verse 1, the high string idea plays 4 times, in the 2nd third of Obie Trice’s 24 bar first verse. This adds interest to something that would otherwise sound more boring. The cello idea, however, is important because it repeats EVERY 8 bars (never coming or going). By doing so, it is an important structural demarcation line for sections in the song because all of the sections in the song are based on a number of 4 bars: they consist of 24, 16, 8, 4 etc., bars. Thus, the cello staccato idea marks the end of one section and the beginning of another, or the midway section of a section (like the verses.) Once again we see a hierarchy, this time of structural function. All of these different aspects of the music (structure, pitch, rhythm) are imbued with a perfect proportion by Dre. None overpower each other, and they all act in such a way that together they are more than the sum of their parts.

Now if Dre had stopped there, that would have been enough. But he is a noted perfectionist, so he takes it to the next level by giving the 2nd and 3rd verses their own characteristic ideas. In the first 8 bars of the 2nd verse, we get the following idea played by a guitar:

This guitar is played in standard E tuning of a guitar dropped a semitone, so that the guitar is then tuned in Eb. This allows the above musical idea to be played on an open Eb minor chord. This idea, a 4 bar idea that repeats twice, is a true arpeggio of the tonic Eb minor chord. It covers a much wider range than the other ideas, but because it is an arpeggio and does not have any notes that aren’t part of the tonic chord (it’s all Ebs, Gbs, and Bbs) it can fit very easily into the vertical pitch range of all of the musical ideas over the 2 bar bell idea so that the two do not conflict. This guitar idea is kept in the higher range so that it’s easier to hear. Furthermore, the high violin idea is absent, because having both would be an overload of musical information (note that as soon as the guitar idea ends, the high string idea comes back in.) This idea differentiates the 2nd verse from both other verses. Dre likewise differentiates the 3rd verse from the 2nd and 1st with the following idea:

This 4 bar idea is repeated 4 times so that it takes up the entire 16 bar 3rd verse. It is played by a solo violin. Note how it fits into the vertical range of pitch with the other ideas: its highest note (Gb) is the lowest note of the bell idea (never overlapping), while it’s lowest note (the Bb) overlaps by a single semitone the piano idea. Thus, we see more of the same balancing. This idea too is strongly in Eb.

The one idea we haven’t mentioned is the 8 bar contrabass idea that is a riff on the rhythm of Busta’s words in the chorus (or the words in the chorus’ rhythm is a riff on the contrabass idea, whichever you prefer.) The contrabass music fits in with our earlier theories, in that it’s notes occurs in the octave below the staccato cello, keeping the range of music still even.

This brings our total number of different ideas to 8 – the piano idea, the staccato cello idea, the contrabass idea, the high violin idea, the solo violin idea, the acoustic guitar idea, the bell idea, and the bass/snare drum idea. It is not enough that there are 8 different musical ideas, and that’s what makes this song amazing. It’s that so many different ideas are in perfect proportion to each other, in terms of pitch range, rhythm, and structural importance. They do not distract from each other, and the ear can very easily follow each one. Furthermore, some idea s, like the guitar and solo violin idea, serve to differentiate each re-iteration of a standard section of a rap song (verse/chorus) from the others.

I got tired of doing rap verse analyses, so I decided to try something different. I’ve got some other Dre songs in mind for more musical analyses, so there might be more of these. Hope you enjoyed this rap music analysis!

If you liked this article, you might enjoy these other ones, which are among my most popular:

1.) An analysis of Nas’ flow on the 2006 Busta Rhymes song “Don’t Get Carried Away,” which you can read here.

2.) My album review & analysis of the 2012 Kendrick Lamar album “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” which you can read here.

3.) A database of who the 23 most repetitive rappers in the industry are, available here.

4.) A study of every instrument Dr. Dre used on his songs between the years 2000 and 2009, online here.

5.) A breakdown of Eminem’s song “Business,” which you can check out here.

Dude! I want to see the sixteen pages of sheet music for it, just 'cause I'm weird (but no weirder than the guy who wrote out sixteen pages of sheet music, haha). Can I get that somehow?

This is amazing. Okay so here I come as the avid sample chaser yet again, it's alleged that Dre sampled, or at least mimicked the piano idea from the English electronic band Depeche Mode song "Precious" (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7eD2Gy8uKg), heard at 0:14 and throughout. What are your thoughts on how Depeche Mode incorporated the piano idea into their production? Perhaps comparison and contrast is in order?

Yo man, good idea. Tracking the samples yet again. I just checked the dates of the songs, though, and they're off. The song the sample comes from, "Oh!", is off Obie Trice's 2003 album "Cheers". Depeche Mode's album that "Precious" comes from, "Playing The Angel", is from 2005. It's funny though, the samples are exactly the same. I guess if anything though you could say Depeche Mode sampled Dr. Dre!

WOW, great catch. I completely neglected to check the release dates on the Depeche Mode album. That makes it all the more interesting. I say this because when certain critics cite the "problem with sampling" they bring up hip-hop alone. In reality, many contemporary genres have incorporated sampling into their production scheme, like electronic music for example (see: Daft Punk).

You did an amazing job with this. It read like I would want a music textbook to read. All very simplistic, intuitive language and an assumption of a naive student. You also make explicit some really core ideas and lay out some guidelines for making good rap beats. When you put it down in writing like this, it really sticks. Again, superb analysis. I want to see more, maybe of a song that I've heard of before. Try an Eminem beat next, if you don't mind.

Thanks a lot Josh, that really means a lot to hear the kind words you have to say. I will take a look at an Eminem beat sometime – funny enough, he was basically schooled in production by Dre when he came up on Dre's Aftermath label, and so his production is similar and different, each in important ways. Also, I am in fact writing a book, but I'm having a little hard of a time trying how to translate this electronic format of a blog that works so well with free educational use of songs and such into a paperback format, but we'll see.

Thanks again!

This is a good post. I'm definitely going to look into it.Really very good songs collection you have nice stuff i love it……………..

new rap songs

Thanks man! If you'd like this you'd also like the one on Dr. Dre's orchestration. I'm gonna try to do more analysis of beats in the future, but they're more difficult than rap ones to do, haha. Thanks for the kind words!

Great, awesome analysis.

Thank you sir! Any song you want me to take a quick look at for you? Email me at [email protected]

Wow this is really awesome. I never thought to think of a beat in such a way.

I think one of the craziest beats I've ever heard was that of Monster by Kanye West on MBDTF. Is it possible for you to make an analysis of it?

Sure brother, email me at [email protected] with your question and I'll do it up

This is a sweet blog. I really love this song and pretty cool to see someone take the time to analyze it. Well done!