After last month’s article on Kendrick Lamar, found here, let’s take a look at a different rapper for this next rap music analysis. This time we’ll be looking at Nas’ 2nd (and only) verse on one of his most recent collaborations with Dr. Dre, “Don’t Get Carried Away,” although the track comes from a Busta Rhymes album. (If you like Dr. Dre’s production style, maybe think about reading my article on his choice of instruments after his Chronic: 2001 album here.) It contains two of my all-time favorite moments in rap music. To do this, we will use the same techniques that we did in the Game and Eminem analyses to investigate some of the same areas: for instance, where the accents in fall in the bar, and what exactly should be counted as an accent. However, the answers we get this time won’t be as clean and tidy as the ones we got in Eminem and Game. In a way, it’s fortuitous that the Game and Eminem analyses were the first ones that I did. I don’t think I could even begin to have understood Nas’ music without knowing what the Game and Eminem analysis articles taught me; you can read Game’s here, and Eminem’s here. Stick around for this one first, though!

**A quick note: towards the end of this, things get pretty complicated. But I promise, if you stick with it and work through it all (I explain it in pretty painstaking detail), it will be very, very worth it. And I’ve included the full sheet music of the verse at the bottom of this post, just scroll down to it if you ever need to clarify something for yourself that I make reference to.

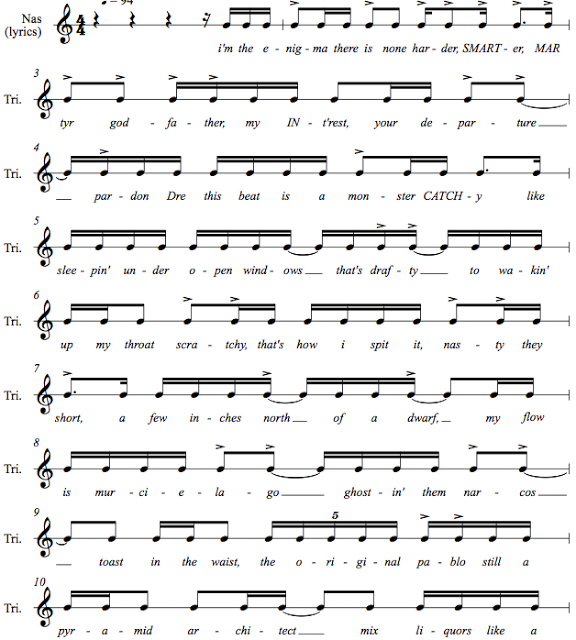

Nas begins the verse with the first of the two favorite moments in rap music of mine that are in this song. Right off the bat, Nas utilizes a certain type of accent that we saw in the Eminem analysis: assonance. That is, the repetition of a vowel sound will cause a certain note/word to stick out in the listener’s ear. Here, it is starts with the middle syllable “nig“ on the first beat and is then reflected in the same place on beat 2 (that is, right on the beat): “is”. Next, Nas begins his first extended poetic grouping: harder / smarter / martyr. A solid, fairly complex rhyme to execute (sidebar: how hard or unique it is of a rhyme that a rapper uses should also be considered when assessing how good they are. For instance, Em did accent a single syllable more than once a beat in the last verse we took a look at, in “Business”, but let’s be honest: he was very smart in his choice of the syllable he did accent so much. That syllable is “ee”. There are TONS of words that have an “ee” sound. Just sayin’.). But the rhyme has nothing to do with one of my favorite rap moments of all time.

But first, let’s do a quick summary of our discussion of accent so far. (I strongly encourage you, if you haven’t read the Game or Eminem articles yet, to go back and read them now. I do my best to catch you up on it as we go along, but I explain these things more in-depth in the other articles.) So far, we’ve identified different levels of accent. (Accent can of course first be defined as emphasis on a musical note.) First, there is the “metrical” level of accent. This metrical level of accent is the accent that the music’s time signature gives to the bar. In most rap, which is in 4/4 (meaning that there are 4 quarter notes to a bar), that means that the accents of the bar, on beats 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, will be the following: 1 (very strong) – 2 (weak) – 3 (also strong, just less so) – 4 (weak). The musical space in between these beats then varies in their amount of syncopation. (This fact we saw was important in the Game analysis, when we saw that his variation of the accent between his first 8 bars, when it was right on the the beat, and his second 8 bars, when it was the 2nd sixteenth note, was especially felt by the listener because they contrast so greatly in how accented they feel in the musical 4/4 bar- that is, the 2nd sixteenth note is very syncopated, while the on-the-beat note has a very strong accent.)

The next level of accent is what I have termed the “poetic” level of accent. This is formerly what I’ve referred to as the accent of the rhyme (or the rhyming accent, etc.) I’ve changed to the term “poetic” because it is more all-inclusive for our purposes here of determining what notes are accented and which aren’t. We’ve seen that rhymed words have accents (for instance, from Eminem early on last time, “FREE-LY.” The capitalized syllables are accented because they rhyme.) However, also from Eminem, we see that there is another way of accenting words: that of assonance, or the repetition of a vowel sound (again early on from Eminem last time: the “see” and the “-cee” of “emcee” are accented because of assonance.)

However, it is time now that we consider a third level of accent that Nas brings to our attention: that is the level of what I call “verbal” stress. That is the accent of how people say certain words. For instance, the word “harder” has its accent on the first syllable: “harder” . (You can check for yourself the rest of the accents of these words at dictionary.com if you so desire. Also, I’ve reflected the verbal accent of words in the notation below by capitalizing the letters in the syllable that is accented whenever the verbal accent is displaced from the metrical accent.) Now, almost all of the time a rapper will always abide first by the verbal accent of the word when placing the notes in their respective places in the musical bar (from Game, 2nd bar: “chrome hy-DRAU-lics”: the capitalized syllable is on the beat and thus, it’s verbal accent matches up with the bar’s metrical accent.) And when the rapper doesn’t abide by the true verbal accent of the word, he simply changes the verbal accent of the word to fit with the metrical accent: early on, from Game again, 3rd beat: “IM – pa- la”, when normally the accent of the word impala is on the second syllable: im – PA – la.

But what if a rapper were to purposefully displace the real verbal accent of the word (im – PA – la) so that it WASN’T right on the beat? Hm… this is exactly what Nas does. He lines up the verbal accent and the metrical accent exactly the first time around (e – NIG – ma: the “nig” occurs on the beat), and does the same on the next multi-syllabic word (one syllable words obviously are only one or the other, weak or strong, so we don’t consider them here): “HAR – der”: the “HAR” occurs on the beat. But with the notes of “smarter”, he doesn’t line up the verbal accent of the word (SMAR – ter) with the metrical accent of the musical bar, which occurs on the syllable “-ter” of “smarter”. Game and Eminem never did this. Nas does it again in the next beat, when he says “MAR – tyr.” To align the verbal accent of the word with the metrical accent of the bar he would have had to have said “mar – TYR.” Now, pronounce that to yourself. It sounds very, very different from how the word should be said, and seems very awkward once it is pointed out. But Nas does this twice, and when you listen for it, it throws the cumulative level of all the accents WAY out of whack. A huge level of contrast is created by a strong verbal accent (SMAR – ter, MAR – tyr) being displaced from a strong metrical accent (remember, that 4th sixteenth note of a bar feels very syncopated metrically), and is so unexpected but also awesome-sounding that we finally have arrived at one of my favorite moments of rap music. Just listen for it a couple times over and over again. Again, we never saw this kind of thing from Eminem and Game, who would have changed the verbal accent of the word to align with the metrical verbal accent: smar – TER, mar – TYR, which would have been very awkward. (And during all of this, at the poetic level of accent – rhymes, assonance, and other types that we will identify – all of the words are rhyming: harder, smarter, martyr.) Nas continues to do this throughout these first 3, through-composed bars: the verbal accent of the word “interest” (“INTR-rist”) does not line up with the metrical accent of the musical bar (which matches up with the –rist of int’rist.) Also, the verbal accent of “catchy” (CA-tchy) does not line up with the metrical accent. (Although, just as an example, Nas does change the verbal accent of one of the words in these bars to match the metrical accent: for “godfather”, he says “god – FA –ther”, although this sounds much less awkward, due to the fact that he divides this compound word along it’s component elements: “god” and “father.”)

Now, let’s turn to another way of analysis of a rapper’s flow that we used in our last two analyses, the area of phrasing. Take a look at Nas’ first 3 bars, and tell me if you can find any phrases, that is, small rhymthic groupings that are repeated over and over to give a verse structure, like that of

Eminem’s:

![]()

or Game’s:

Take a look.

Nothing?

Exactly. And here, we get to a great reason for why I consider Nas one of the greatest rappers of all time, and possibly the greatest technical rapper ever. Nas is considered so complex because he greatly undermines with his rapping what I’ve heard termed in pop music the “tyranny of four.” Think about it. How many beats are there in a bar? 4. How is a beat divided? By 2 (and 2 x 2 = 4) – quarter notes, eighth notes, sixteenth notes, etc. How many bars are structures of a pop music almost always (99% of the time probably)? 16 or 8 (or divisions of 4 within these, such as 8, 12, 20, 24, 28, etc.) It gets very tiring when you notice it after a while. This is why many classical listeners cannot stand to listen to pop music: everything is repeated over and over in multiples of 4, but classical composers are always changing up the structure of the bar and phrases. Wouldn’t it be refreshing if a rapper didn’t abide by these rules?

And that’s what Nas does. He doesn’t abide by the tyranny of 4 like Eminem and Game do. For instance, how many beats does Game’s phrase last? 2 (which is half of the 4 beats in a musical bar). How long is Em’s phrase (4, the whole bar, repeated 8 times, 8 = 4 x 2). But Nas doesn’t always use phrases. Sometimes, he creates the rhythm of the poetic accents of his verse all the way through, one at a time, which is why I’ve termed it “through-composed.” Look at his first 3 bars: there is no discernible phrase that is repeated over and over, like you could see in Game’s and Em’s verse. This constantly keeps the listener guessing as to what note/accent is coming where next (and is very complicated comparatively indeed.) There is no repeating of a musical idea lasting a multiple of 4 beats in a phrase repeated another multiple-of-4 number of times. And because of this, you never know where the poetic accent is coming next. You can describe it more accurately like this: when considering the accents of Game and Eminem, although you don’t know when or where the poetic accent (again, the notes with rhymes, or assonance, are accented) is coming next, you know generally where to expect it because of the nature of phrases: they are repeated over and over. So although Eminem varies the accent in his phrase, every time (except two of them) does he place the rhyme any place other than in the metrical places in the notes of the prototype phrase we identified above. (Game has similar statistics in his own placement of rhymes outside the confines of his phrase.) But with Nas, you don’t know where the accent is coming next and you have no idea where to expect it. This is very different and very refreshing once you recognize it.

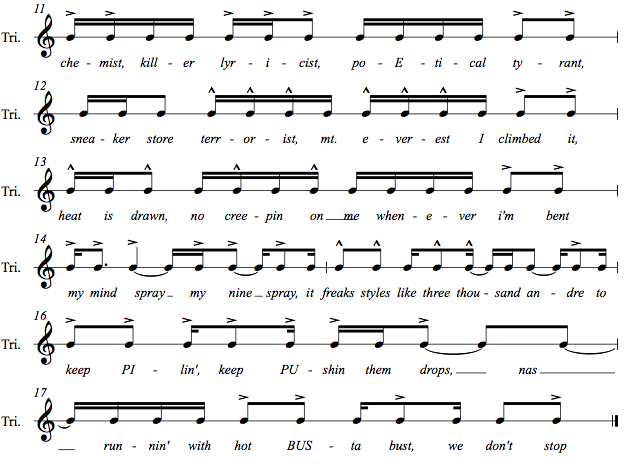

And once Nas does use phrases, he places them at a structural point in the verse that is not a multiple of 4 or the number two, which likewise breaks up the monotony of that “tyranny of 4”. For instance, Nas begins to use a phrase (the notes from “pardon Dre…” to “catchy”) at bar 4, which does not submit to the “tyranny of 4” rule (which, if it were to submit to it, would have the phrase placed at bar 5, which divides the 16 bars structurally by 4.) So although he starts using phrases, which could become repetitive, he does it in a way that makes it flow seamlessly. And, although he uses this phrasing for 4 bars, he sets the phrases up in a very interesting way: A b b, A b b, with the A’s being the same phrase and the b’s being the same phrase, and the A’s being 1 bar long and the b’s being only half a bar long. And like Eminem, he varies the placement of the poetic accent in the bar in corresponding phrases. Take a look at the As. In the first A, the poetic accent (the “drafty” that rhymes with “scratchy”) occurs on the 2nd 2 sixteenth notes of beat 3, while in the 2nd A phrase, the poetic accents (the rhyme of “north” with “drawf”) occur in different places: on the 4th sixteenth note of the 2nd beat and the 4th sixteenth note of the 3rd beat. And examine how Nas lines up his corresponding poetic groupings (a poetic “grouping” would be a group of words that make accents off the same syllable, for instance, from Eminem, first full bar, “BREATHES so FREE – LY,” which is a combination of assonance rhyme; breathes – freely is the poetic grouping.) Here, in the first A b b iteration, there is a full poetic grouping on drafty, scratchy, nasty. But in the second A b b phrase grouping, all of the poetic groupings are different : (north/dwarf in A, and lago/narco in the 2 b phrases following it. And there’s no way Nas did that by accident… damn. )

Let’s look at another element of Nas’ undermining of the tyranny of 4 in his treatment of the first beat of the bar. Now, all of Game’s and Eminem’s adherence to the number 4 when creating structure in their verses puts a ton of emphasis on beat one. A new idea always begins on beat 1 when the phrase is repeated. This greatly separates each bar from the next. But Nas doesn’t treat beat 1 as a definite, fact-of-law arrival point. He runs over beat 1s when he extends his phrase from the previous bar. Observe: end of bar 4, “to wakin UP my throat scratchy”- he doesn’t start a new idea on beat 1. This is endemic of a general different treatment of strong metrical accents by Nas throughout this whole verse. Eminem and Game create the forward motion of their verse through rhythmic syncopation: they thrive on avoiding the strong downbeat, and then hitting it later on. Observe even how Eminem’s 1 bar phrase in “Business” is constructed: half a bar of strong syncopation matched only by a half bar of strong, on-beat, motor-like rhythm. And, of course, there is the contrast between Game’s 2nd sixteenth note hit and his on the beat hit. Nas’ rhythm, however, is different. He doesn’t mind landing on the downbeat consistently: bar 10 – 13, he hits 14 consecutive on-the-beat notes. Eminem or Game would never do this (they’d do this at most 3 or 4 times in a row.) It’s almost as if Nas is just talking and consistently going (although Nas also does at points like Game and Eminem contrast syncopation and on-the-beat accent, see bar 4: “open windows that’s drafty to wakin’”, all of which avoids being on the beat and propels the music forward strongly).

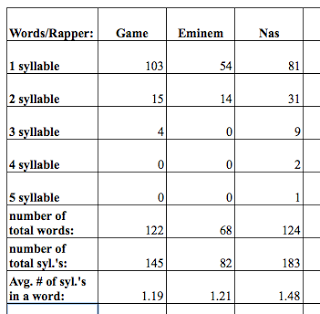

After the full A b b, A b b phrase grouping is done, Nas goes back to the through-composed writing style. Here, I’d like to address another point of Nas’ rhyme: how long the words he uses are. For instance, from bars 8 – 11, he uses the words pyramid, architect, lyricist, poetical, terrorist, and everest. It’s not a consideration of how highbrow the words are or anything, but only a consideration of how many syllables they have: all of them have 3 (except poetical, which has 4). Compare the following statistics:

That is a statistical breakdown of the number of words in each of the rapper’s respective verses with 1 syllable, with 2 syllables, etc. If you follow the data you can see that Nas’ words have on average more than a full quarter of a syllable. What’s more is that Nas is the only rapper among the group who uses a 4 or 5 syllable word, while Eminem fails to use a 3 syllable word at all. Now, to be fair, each rapper here has his own different goals. Eminem wants to show off his aggressive rhyming ability, so he’s just trying to squeeze as rhymes as possible into as small a space as possible. Nas and Game aren’t trying to do this.

Also, consider how Nas structures his poetic groupings. In bars 10 and 11, he fits one poetic grouping inside another poetic grouping – “tyrant” matches up with “climbed it” on each bars beat 4, but while that occurs, Nas fits the poetic accent grouping of “terrorist, everest” inside it. (This is reflected in the notation by a secondary accent marking, the tiny hat). Bars 10 through 12 are united in the repetition of a bar long phrase, unified by the poetic groupings on 2 eighth notes taking up beat 4 (I feel like there is not enough information here to make a prototype phrase.) Again, this phrasing starts at a structural point in the verse that is not a strict multiple of 4 (bar 10), and lasts only 3 bars long (the initial A phrase repeated twice.) And now we get to my second favorite moment in rap music that is in this song, another undermining of the tyranny of 4 by Nas.

With this, Nas takes the idea of phrasing to a whole other level. If you look at bar 12, you will see a rhythmic idea repeated (i.e., a phrase):

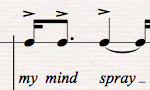

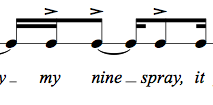

That music above is an example of the phrase. It is one sixteenth note, followed by a dotted eighth note, and the hitting of another note at the end of that. We will see, however, that we cannot definitively define the length of that last note because of what Nas does with the phrase next. He displaces the phrase metrically in the bar, moving it a sixteenth note after where it appears on beat 1:

In the above music — as reflected by the beaming of the notes, which are those things that connect them across the top — the first sixteenth note of beat 2 is actually tied to the end of the word “spray.” It’s a little hard to see in the picture, because you can only the see the “y” and the end of the tie, all the way on the left. What’s more, is that Nas has moved the phrase to begin on the 2nd sixteenth note of the beat. So although they do not look the same because they are notated differently (as a result of the beaming of the notes to reflect the basic beat of the bar), they are actually still notes of the same duration: a sixteenth note, followed by a note with the duration of a dotted eighth note, followed by another note (check it for yourself). Notice that this displacement of the phrase by a single sixteenth note radically transforms the rhythmic function of each note in the phrase. The first time around, “my mind spray”, that first single sixteenth note (on “my”) falls right on beat 1, so it sounds very strong, while “mind” is very syncopated (and “spray” falls right back on the beat after that.) But by displacing the phrase a sixteenth note, that first sixteenth note of the phrase (again, on “my” the second time) assumes the role of a pick-up note (a pick-up note is a note that falls before another note and serves to emphasis the note it comes before. “Just to get to” is an example of a full beat of pick-up notes in the Eminem analysis we just saw; they’re the very first words he says.) The “my” sounds like a pick-up note to the “nine”, because although “mind” (by virtue of its falling on an eighth note in between the beats of the bar) is still technically syncopated, it is much less syncopated then the sixteenth note that the “my” that comes before falls on; as a result, you have the pick-up feel from “my” to “nine.” But this is only the set-up for what is my 2nd all-time favorite moment in rap in this song.

The thing is, he does this twice.

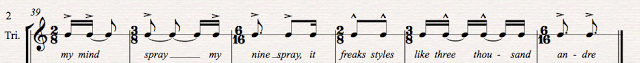

Due to music’s unique temporal nature (that is, the fact that what we hear in the present is able to re-interpret what we’ve already heard before while at the same time anticipating what is to come), when we hear this displacement of the phrase again in bar 14, “freaks styles…andre”, it re-characterizes how we heard it the first time around (in bar 13, “my mind spray, my nine spray”). If he had simply placed the “-dre” of “andre” in bar 14 back on the beat, on beat 4 (as I actually had notated it the first time I tried it,) the unique and unusual placement of the notes in bar 13 on “nine” and “spray” could have been explained away very easily by saying that they were setting up a syncopation that was very soon later on resolved with a strong downbeat from the rapper, as we’ve seen Game and Eminem do over and over. But because he does it twice, he actual changes a fundamental way of how we hear the rap. I would really notate these two bars like so:

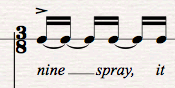

Now, this may look like nothing you’ve ever seen before. But don’t immediately think “I don’t know what the hell’s going on here!” Let’s just do the math. Each 2/8, 3/8, 6/16 time signature grouping (there are 2) really just adds up to one bar of 4/4 (2 8th notes = 4 sixteenth notes, 3 8th notes = 6 sixteenth notes, add those 10 to the 6 sixteenth notes of the 6/16 bar and you get… 16 sixteenth notes, exactly equal to one bar of 4/4.) Those different time signatures just more accurately reflect how the beat of the music is being felt. Let’s do a quick review of time signatures. The number on the bottom is the beat of the bar, and the top number says how many beats there are in a bar. So, in order, above, there are 2 8th notes, and then 3 8th notes, and now we get to 6/16, and why I’ve notated it as 6/16 and not 3/8. See how in the way I’ve notated it above the beat of each musical bar is reflected very clearly by the beaming of the notes? It’s very easy to see in the above that there are 2 8th notes in the first bar, and then 3 8th notes in the 2nd bar. That’s what good music notation will do. It will make it easier for the performer to perform. That is why I couldn’t notate the 6/16 bar in 3/8: I would have had to break up the beat when notating it in 3/8, like so:

This notation is awkward because half of our main rhythmic information (the note of “spray”, as the “it” is really just a pick-up note to the next bar) doesn’t land on the beat, and a full beat is awkwardly tied over. But in 6/16, it does. Interesting to note that as a result of this, Nas has broken us out of our strict duple meter time signatures in 4/4 and 2/8 (duple means that there are 2 or some multiple thereof number of beats in a bar), into triple meter time signatures (which means that there three beats or a multiple thereof number of beats to a bar) with the 3/8. And by moving from the simple time signatures of 2/8 and 3/8 (“simple” here is a technical term, meaning that the beat – the eighth note of the 2/8 bar above, for example – is subdivided into two equal parts, as when going from an eighth note, to a sixteenth note, to a thirty-second note, etc.) to the compound time signature of 6/16 (meaning that the beat is subdivided into 3 parts, not 2 parts like simple time,) he is really venturing into some amazingly complex rhythmic areas in rap.

After this amazing moment, he continues with his through-composed style of writing, with no clear phrase structure repeated over and over. It might be noted that here, just as how he began the verse, he ends it by displacing the verbal accent of the words ( PU –shin, PI – lin’) from the metrical accent of the bar. A note should also be mentioned here as to some of the reasons for why I’ve chosen to accent certain notes in the verse that aren’t yet accurately reflected in my notation of the verse. The critical information I’ve left out of my transcription is how Nas actually says the words; for instance, he doesn’t pronounce “godfather” with a perfect accent, he says “gawd-fawther”, because that’s just the way he speaks. This allows two words like “martyr” and “godfather” to be accented together, because although they shouldn’t really rhyme together when perfectly said, Nas’ way of speaking allows them to. So whenever you see notes below accented that don’t seem to rhyme, go back and listen to how Nas actually says the words; it will probably make sense then.

Finally, we should add that Nas doesn’t end the verse anticlimactically or anything either. He makes the very last eighth note of the 4/4 bar (the note on “stop”) accented (in assonance in a poetic grouping with the words “hot” and “drops” that come before). With that last eighth note being in the syncopated metrical position that it is, when Nas does this, he allows his own verse to lead very strongly musically into the chorus, by having beat 1 of the chorus complete his musical idea with its strong downbeat. This is what a good rapper will do. He will tie two different structural parts of the song together.

And let’s remember that Nas has had very little formal musical training (if any at all.) And the fact that he’s able to do this makes him an unqualified musical genius, no matter the arena of music (popular, classical, etc.) I’ve taken multiple years of music theory analysis classes and I’m still grasping to get at some of the things he’s doing. (I mean, simple, compound, duple, and triple time signatures? I’m literally speechless…) I think Nas has more than earned his money. And also let’s remember that all of this occurs in no more than 16 bars, or about 40 seconds.

Pretty amazing isn’t it? Now, unfortunately I think I copied over my complete notation of this verse, so I’m left with only the normal 4/4 notation of the 2/8, 3/8, 6/16 time signature bar grouping we went over. But remember, it should be notated the other way. I’ve tried to explain everything in as painstaking detail as I can. If you’re still a little lost, I suggest wiki’ing time signatures. It will explain everything you need to know.

Thanks for checking it out! Like I said, I erased my newest versions of some of the sheet music (which is especially annoying because I was very afraid this would happen and did my best to avoid it,) so some verses (like Eminem’s “What’s The Difference” which is possibly even more mind-blowing than this one and will be well worth the wait) won’t come out for longer than I expected.

Hope you enjoyed this rap music analysis! And if you did, you might like this other one I did here, which is all about which rappers are the most repetitive…Yes, you’re right, both Lil Jon and will.i.am ARE on it!

P.S. – I teach people how to rap, so if you want to learn, hit me up. Just consider this post my resume, to go with my start video for new, aspiring rappers here.

Great article! Lucid and thoroughly enjoyable.

you should listen to the songs "legendary" and "heaven" by Nas too, the second verse on "legendary" is amazing in term a complex rhymes

Wow, this is a very good write-up. Looking forward to reading the rest of them. Rapgenius' MF Doom Flow Encyclopedia brought me here

Thanks! Think about buying the book man, it'll keep bringing you good shit like this.

Thanks again for the compliment

Would love to see any write ups on eLZhi, Black Thought, or Aceyalone. They are some of the most technical rappers I know. ANTHM is very good too: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXNWNMxAKLk

Quick question. When you rap on beat, do you write on rhythm notes or is it based on the instruments?

It depends on what the MC is goin for. Sometimes I write to the notes, sometimes I ignore them. Others I balance between matching the music elements and just goin off the feel the music gives me. I hope that helps…

Does Nas construct all his rap songs this way? Because his rap has rarely repeating flow, it seems like it would be difficult to perform live.

>Does Nas construct all his rap songs this way?

From the ones I know (his Aftermath work, Illmatic, some Stillmatic,) he makes a lot of his songs this way, which is called through-composed. That's a technical musical term, and basically means that the music has no small repeating elements, like you astutely point out:

> his rap has rarely repeating flow

>it seems like it would be difficult to perform live.

I think you're absolutely right. It might be difficult for you or me, but not for Nas, haha. He is one rapper who seems to have a really great live performance; he was good enough to hang with The Roots at the summer concert they do in Philly every year, when they remade the entire Illmatic album live. If you want a good live demo of just how finely crafted and subtly different a rapper's rhythms can be from one moment to the next, check out this exact transcription I did of Earl Sweatshirt's rhythms here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GRbhQzVtT84

Thanks man! If you want a weekly newsletter with articles like this, on which you will never be spammed (for which I would commit seppaku,) email me at [email protected]

Thanks for commenting!

Love,

Martin

Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Centri Records is a New York based independent record label owned by Rhandy Acosta. It originated as a way for local talent from Queens, NY. Rhoyale’s new single Tonight is now available on Apple Music and Google Play. Add it to your playlist today.

Thank you very much for keep this information. sham idrees nayab

You're wlecome! Sorry so much for the late reply; don't know how I missed this. But if you hit me up at [email protected], I'll DEFINITELY make it up to you, with some free materials and goodies 🙂

Best,

Martin

P.S. – Thanks so much, again, for your compliments!

Can you analyze one Mic by nas; specifically the last verse? To my untrained ears, it sounds through composed with no clear, predictably recurring accents. Curious about what you think!

Sure! If you email me at [email protected] I'll get back to you with a reply for sure. Thanks man!

Best,

Martin