Over the summer, I had the opportunity to meet George Crumb, a very well-renowned composer who would be found in any textbook on contemporary or 20th-21st century music. It all started when I watched a documentary on Igor Stravinsky (certainly one of the titans of classical music), and he recalled in vivid detail a childhood experience that greatly affected him for the rest of his life. He recounted a time when as a young child he went to a concert and he saw Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, a great Russian classical composer of the Romantic era. I thought to myself, I want to have an experience like that! Luckily, I reside in an area where there is a lively classical music scene, with concerts, operas, etc., held regularly, and with many pre-eminent educational institutions in the area. Surely, I would be able to find someone in the area who I could meet. And indeed I did.

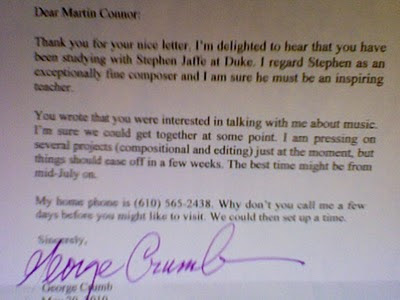

I first went to check the alumni of the music schools in my area, and decided to try and meet one of them. The composer I came upon is a composer by the name of George Crumb. Crumb was born in Charleston, West Virginia. He received his degrees from Mason College of Music, University of Illinois-Champaign, and then the University of Michigan, before he began a long-term relationship with the University of Pennsylvania, where he taught from 1965-1997. Because Crumb has been so widely published and celebrated, he is one of the few composers who has made enough money from writing music that he did not need to teach (as almost all composers do today.) However, he chose to do so anyway. He, in turn, taught many talented and accomplished composers who write today, including a teacher who I took a class with before, Prof. Stephen Jaffe. Crumb liked Penn enough that he decided to remain in the area, and has done so until today. I looked him up online, and found an address. I sent him a letter, asking him if he’d like to meet. I received the following letter in response:

Eventually, I got back to him, and we set up to meet on a weekday in July.

I pulled up a house that looked pretty unassuming. Now, I should make it clear from the outset that I had no idea what to expect. If I was going to meet the equivalent of George Crumb in another field, like a famous rockstar or rapper or something, he or she would live in a giant house, have a ton of money and cars and stuff like that, and there would be no way that I’d get the chance to meet him. However, my meeting with Crumb was no less surprising, or rewarding. The house looked just like every other. I parked out on the road, and walked up to the door and knocked. Immediately, three or four dogs come swarming to the door, barking their heads off. If I did not know that I was at the right address from having dropped off the letter earlier in the month, I would have thought that I was definitely at the wrong house. But a woman came and opened the door for me, the dogs acting up the whole time behind her. I explained who I was and what I was there for, and she let me in. She introduced herself as Dr. Crumb’s daughter, and unfortunately, I forget her name. While we were waiting for Dr. Crumb to come down, she explained that she ran a sort of shelter for dogs. She took in dogs that needed help and kept them until they were ready to go elsewhere.

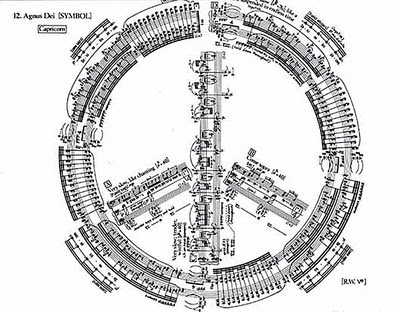

In fact, Dr. Crumb still lives with his wife and son as well, and I met them also. When Dr. Crumb came down, I nervously introduced myself. I was speaking to a man whose name could be found in any textbook on 20th or 21st century classical music. And yet, you would get no sign of this just by talking to him. He was very nice and patient with the questions I asked him when we went into his workplace in the back of his house. At 81 years, he is still going as strong as ever. He seemed very lively and in great spirits, and willing to talk about anything musical. He showed me works that he was currently working on, a song cycle of some American texts. One of the notable things about Crumb’s oeuvre is that it has come out steady ever since he began writing. He has released works in 7 different decades, and I’m sure will soon add an 8th in 2011. It was inspiring to see someone who showed no signs of anxiety at all when it comes to composing. He showed me the tools he uses to work as well. They consisted of many rulers, black permanent markers of all kinds of point sizes, as well as protractors, compasses, and rulers. It was great to see how Crumb produces his beautiful scores, which in themselves are works of art. I was amazed to find out that he does all of them by hand, such as the following one:

I got the chance to ask him a couple questions, such as where he got his inspiration from, what his favorite piece that he had written was, and we talked for an hour or so. I showed him some of the requiem I’m working on. He played through some of it, and made some corrections and other comments. I was delighted to find out one thing in particular, however. If you aren’t familiar with Crumb’s work, he is noted for his exploration of unusual timbres, his use of alternative notation (as seen above), and extended technique. Timbre is the quality of a musical note or sound or tone that distinguishes different types of sound production; it’s what tells a person that a violin is a violin and a saxophone is a saxophone, even though they are both playing middle C. For instance, in his seminal work “Black Angels” (for string quartet), Crumb asks the performers at one point to play crystal glasses filled with water. Extended technique means that he asks performers to do things with their instrument that aren’t very common; for instance, in some works he asks the performers to tap on their instruments. His work is also marked by symmetry; for instance, a work of his might start and end the same way, or the chords he uses are constructed out of the same interval overlaid on top of itself. I recalled this when I was at Dr. Crumb’s when I saw that the piano that he uses, in fact, was (and I presume, still is) out of tune! It seemed like he had been dealing with that (and not just dealing with it, but taking advantage of it) for a while. Almost any other composer would have had the piano tuned immediately. But I think he liked the dissonant sound of it; it spoke to his use of unusual timbres and extended techniques.

Finally, I got him to sign a copy of “Black Angels”, and got some pictures taken with him, which I’ve posted below. I will remember my meeting with Dr. Crumb for a long time. It made me really hope that I get the opportunity to do what he’s done, and it motivates me to take advantage of the chance I have. Hopefully, one day, I will be where he is, working on music, and having young composers contact me to talk!

As a foray into Crumb’s music, I suggest you check out the work I’ve referenced herein, “Black Angels.” Be forewarned, it is unlike anything you’ve heard before! It’s a work for amplified string quartet. Crumb takes advantage of the amplification to get certain effects and timbres out of the instruments that you just couldn’t with their acoustic counterparts. The work is structurally based around the numbers 13 and 7. The Wikipedia page for the work can be found here:

This is the first movement to “Black Angels”, called “Night Of The Electric Insects.” Just click below. Enjoy!

More George Crumb here: http://easyjams.blogspot.com/2011/08/george-crumb-vox-balaenae-1974.html