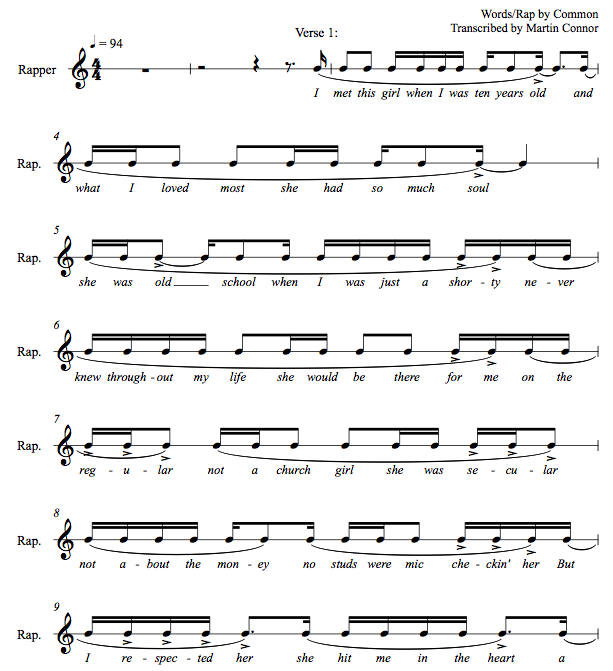

Rap music analysis time! This time we will be switching it up a little, with musical AND textual analysis. However, the two are not separate; we will see how they interact and reinforce each other.

Lately, I’ve been looking a lot at how a rapper structures his

rhythms and syntactic groupings together to reinforce his or her

message. Namely, this comes down to what words he or she accents. I’ll

set out some representative examples in Common’s rap from “I Used To Love H.E.R.”, rated on some lists as the greatest rap song of all time, to demonstrate what

I’m trying to say. (You can here the song here.)

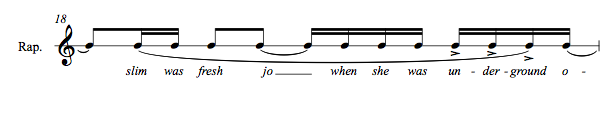

Rappers use a combination of accent (where the word/note falls in

the metrical bar, what part of the word is accented, as well as whether

the word creates an accent with another word through rhyme,

alliteration, or some other way) to reinforce their message. For

instance, the words that Common places on the downbeat of the 4/4 bar

(meaning there are 4 quarter notes to a bar) are words that turn out to

be important in his overall message, which is something along the lines

of “I loved hip-hop back in the day, back when it was only about fun,

and now that it’s become commercialized, it’s lost its ideological

power.” (you might be able to better explain this than me.) An easy way

to do this is to place important words onthe down beats. For instance,

in bar 9 of my transcription, he places the word “heart” on beat 4. This

is an accent of the 4/4 bar; furthermore, he enhances this effect by

making the word further accented by having it rhyme with the word “park”

in the next bar (I differentiate between this kind of accent, which I

call a “poetic accent”, with the “metrical accent” I described earlier.)

Furthermore, he places the note on “heart” at the end of the phrase,

calling attention to it (the beginning and end of any musical structure

or form are structurally important places.) (This phrase is the

syntactic phrase of the grammar of his words; You’ll see that “She hit

me in the heart”, all contained within the phrase marking, forms a

complete grammatical idea.)

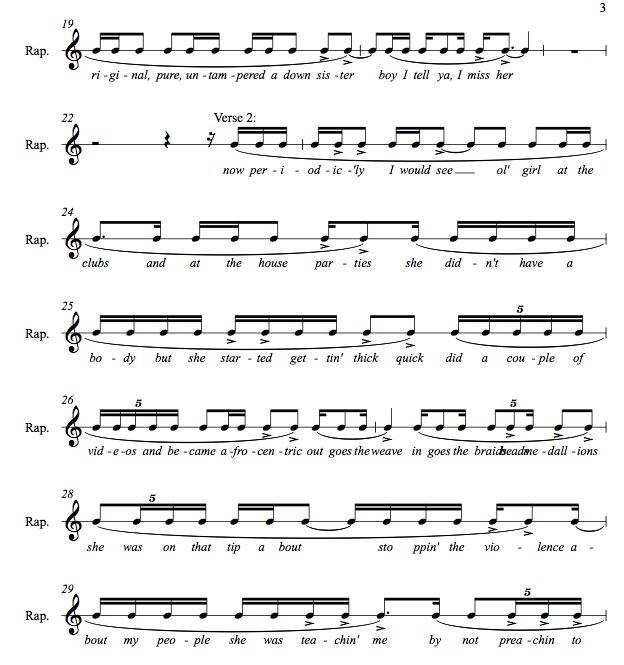

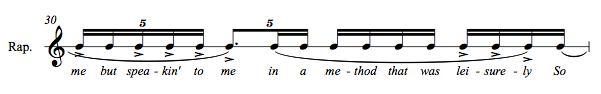

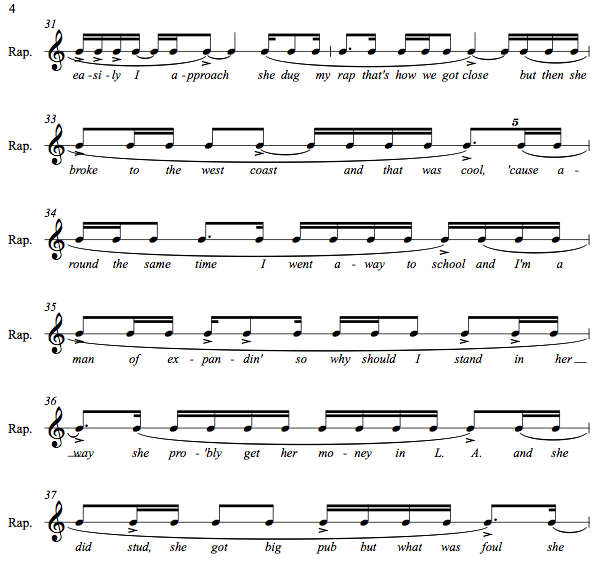

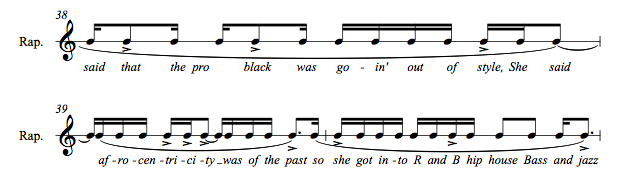

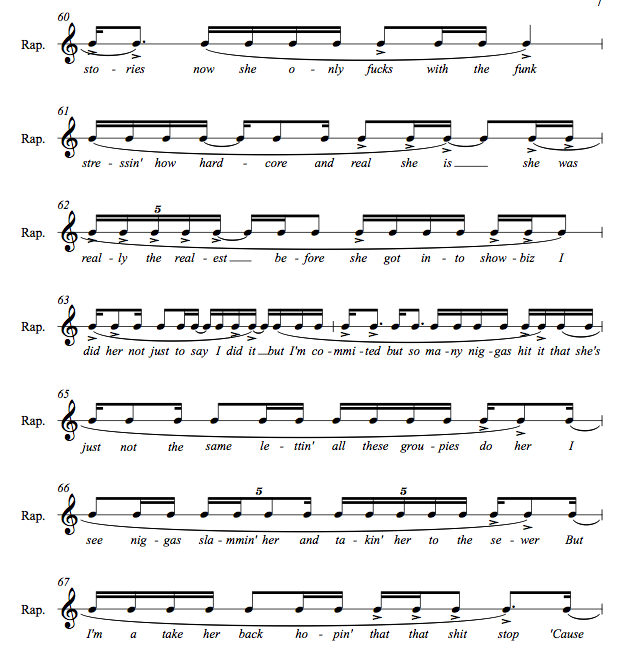

A similar situation can be found on the word “foul” in bar 37.

You’ll see that once again, foul is poetically accented by rhyming with

style in the next bar (although foul and style might not rhyme when we

say them, the way Common pronounces them they do rhyme.) Furthermore, it

is on a downbeat in the bar, and comes at the end of a phrasing. There

are tons of other examples on the level of these ones, such as “cool” in

bar 33, or even “past” in bar 39.

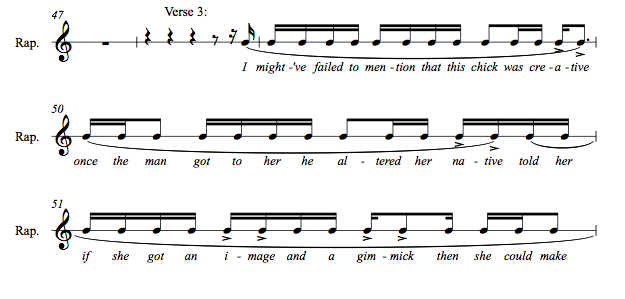

However, these are not even the most sophisticated use of this

technique of bringing more emphasis and force to Common’s message that

he uses. The best example, which is really quite sophisticated, comes in

bar 61, where Common delivers his most forceful and biting message of

all (you might want to describe just what this message is in your own

terms.) He lays it out: hip-hop just isn’t doing it anymore, it has lost

its way, it’s whack. Look at the phrase containing “Stressin’ how

hardcore and real she is”. Through a manipulation of accent as well as

his intonation (here, meaning changes in the pitch of the voice,) we can

see that Common is sarcastically mocking the new wave of rappers, which

would have included the g-funk of the west coast (We know that

Common is indirectly – directly for those in the know – referring to g-funk. He

says in bar 40, “she got into r and b, hip-house, bass and jazz,” all

elements in the g-funk of Tupac and Dr. Dre, and it is made blatantly

clear in bar 60 when he says “now she only fucks with the funk”, as

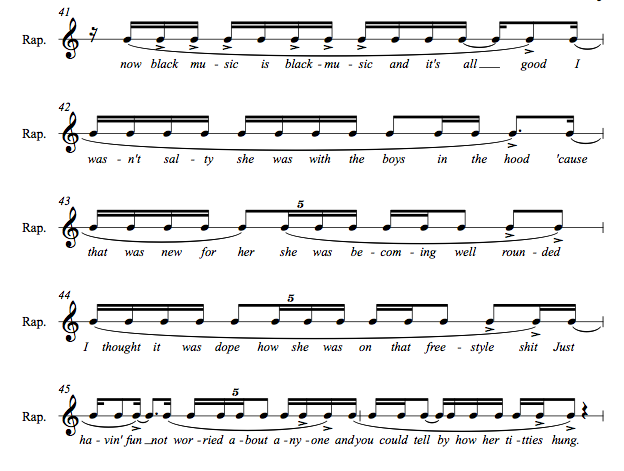

direct a reference you could make to Dr. Dre without saying his name. Furthermore, he uses the phrase “boys in the hood” in bar 42, a famous

movie 1991 movie depicting gangsta life in South Central LA.) You might

cite some other songs that are examples of all of the “popping glocks,

servin rocks, and hittin switches” that Common mentions in bar 57.

I am just trying to give some context for the Common’s comment

“stressin’ how hardcore and real she is.” Now we can see how he delivers

this message. He combines the elements of phrasing, accent, as well as

intonation. He raises his voice’s pitch on the word “real”, and from

this we can detect that he is mocking the use of the word “real” (a

subject which Dave Chappelle has fittingly mocked in his own skits,

something called “when keeping it real goes wrong.) Just like in the

previous examples, we see that Common has metrically accented the word

“real” (it’s on beat 3), as well as poetically accented it by repeating

the syllable “real” in the next bar twice (in “really” and “realest.)

However, that is not what delivers the impact of the message. Common

takes a rather long pause at the end of this message, the length of a

dotted eighth note (3 sixteenth notes all together) that gives the

listener time to think about what he says. He then delivers the

ideological punchline in the next bar, having set up the listeners

expectations for something next to come by ending the phrase with his

voice higher in pitch (like people do when they ask a question.) He

then delivers it: “she was really the realest before she got into

showbiz.” She was really the realest before all that commercial BS.

Common uses these pauses in interesting metrical places in other

places in the piece as well. His quarter note length pause in bar 13

emphasizes his “cooling out.” Just as he says verbally that he used to

cool out with hip-hop (the girl in the song), he musically cools out by

taking a rather long rest, one of the longest in the rap that doesn’t

occur across a barline (where one would normally expect a longer rest,

in order to orient the grammatical units logically within the metrical

divisor of the barline). His phrasing very particularly draws attention

to this, as he takes that rest.

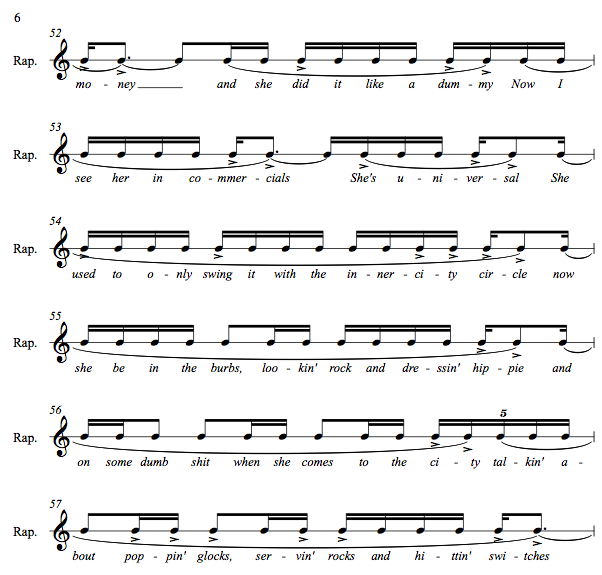

Common repeats this technique in bar 31, when he takes a dotted

quarter note length rest (beat 2 into beat 3.) He says “Easily I

approach”. He thus slows down his cadence (the rate of his accents and

rhythms) at this point to emphasize his easiness musically. He uses a

similar pause in bar 52, a long pause within the bar (a quarter note

plus a sixteenth note duration) that emphasizes the word “money”,

introducing it in ominous terms.

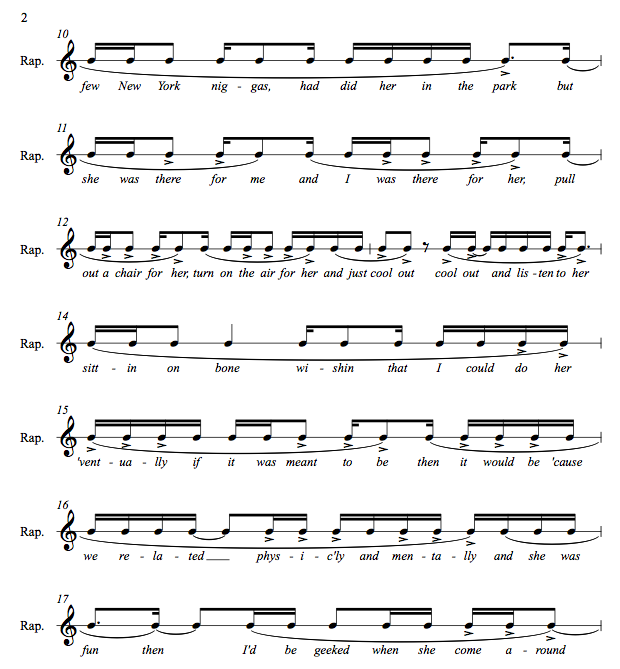

Now for some textual analysis. Common

constantly uses words that could have double meanings when you consider

that Common is talking about music really, not a girl. The most

predictable of these terms is the use of the term “to do”, in context of

having sex with someone. For instance, in bar 10 he says “some new york

niggas had did her in the park”, on the surface meaning that some New Yorkers had had sex with her, but on the next level meaning the New Yorkers had made rap in the park. This is repeated in bar 63: “I did

her, not just to say I did it”. He means having sex on one level, but

really making music on the next. A similar example is nearby: he says,

in bar 63-64, “But I’m committed.” Used in this context, the term

committed has the context of relationship commitment. This works for a

girl, but also for Common’s commitment to music. Old school is another

double entendre; old school typically describes hip-hop cultural

elements from somewhere in the 80s. “Old-school music” is a phrase often

heard in rap circles when describing hip-hop from decades past.

However, in this context Common recontextualizes the word to describe a

human being, which works as well. But when we get to the end of the

piece, and Common reveals that he’s actually talking about hip-hop, we

can see in retrospect that his use of the term “old-school” really has 2

connotations.

Also, Common manipulates the length

of his phrases to emphasize certain areas. For instance, in bars 11, 12,

and 13, bars 29, 30, and 31, he shortens his phrases greatly. In other

places most phrases are about a bar long; in those 2 groupings, they are

more like half a bar. This variation keeps the ear interested in what

he’s saying.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading this rap music analysis!

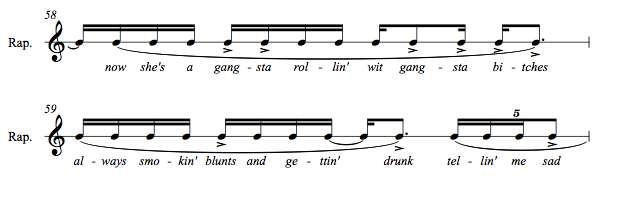

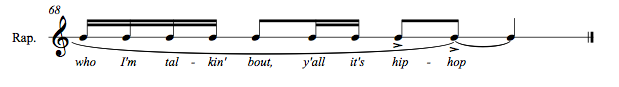

Here’s the sheet music: