This rap music analysis may take some of my readers to musical horizons that they have not seen before. In contrast to other rappers I’ve looked at, such as Jean Grae in my article here, Common in my article here (about his song “I Used To Love H.E.R.”, or Eminem in my articles here, on “Forgot About Dre”…and here, on “Drop The Bomb On Em”…and here, on “Business”…the rapper we will be taking a look at today is very popularly acclaimed. I would like to take this opportunity though to consider the role that single, specific flows play in a rapper’s overall oeuvre (the oeuvre of an artist is considered his or her entire body of work.) Big Sean’s own unique case of a signature flow offers an excellent, very specific example of a phenomenon that is rather more general in the works of other rappers. Furthermore, we will consider whether this phenomenon of having this particular recognizable flow reflects positively or negatively on Sean.

It occurred to me, after listening through Big Sean’s major record label album debut (from Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music label) that, on multiple songs throughout the album, he uses the same flow. First, what elements is flow comprised of? Throughout our analyses, such as my Jean Grae analysis, we can identify the following characteristics of a flow, more or less:

1. Rate of accent – how many poetic accents, such as rhymes, there are per bar –(for a bigger discussion of this, see the Jean Grae post)

2. Nature of articulation – for instance, staying words either staccato (very sharply) or legato (rolling them all together) – credit to Kyle Adams “Flow In Rap Music” paper (don’t worry, it’s very readable – look for point [8]) – for a bigger discussion of legato vs. staccato, see the staccato wiki page or the legato wiki page

3. Nature of grammatical phrases (formerly called syntactical phrases in my work) – a grammatical phrase is the natural musical “grouping-together” that occurs due to grammatical separators, such as conjunctions like “and” or “but”, or punctuation, like commas or periods at the end of sentence. This considers where grammatical phrases begin and end in relation to the bar.

4. Use of musical phrases – whether a musical phrase (a short musical idea repeated over and over) are used or not

5. Nature of rhymes – whether they are isosyllabic or multisyllabic, whether they always occur in the same metrical position from bar to bar or in different places, whether they are internal rhymes (occurring inside grammatical phrases) or end rhymes (occurring at the end of grammatical phrases), and so on.

My thesis is that Sean, on the real “Finally Famous” album (there were 3 mixtapes leading up to it), has a signature flow that is readily identifiable. This is because it’s rate of accent, the natures of articulation, grammatical phrases and rhymes, and the use of musical phrases, are all consistent. I’ve transcribed this flow from 5 different songs of “Finally Famous” album. These songs are “Meant To Be”, “What U Doin’ (Bullshittin’)”, “Supa Dupa Lemonade”, “My Closet”, and “Too Fake.” For a single flow to show up so prominently, being used for extended lengths of bars and at important parts in the song, such as on the chorus, is, in my knowledge of rap, unprecedented. It may not seem like much when you consider that there are may 17 songs on the entire album, but this has to be seen in relation to the great amount of flows there are by a rapper on one album. That is to say, a rapper spits many different flows on a single album; and when one flow shows up so much, it is noteworthy. But more on that is perhaps better for another post.

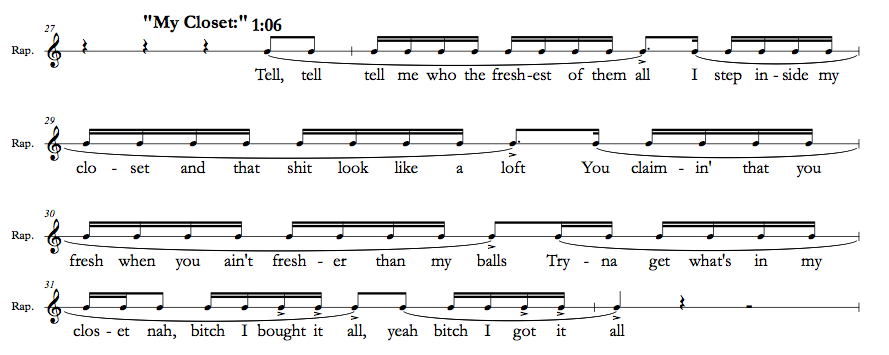

So what is this signature flow? An archetypal example might be from from the song “My Closet”, starting at 1:06, when Sean drops the following 4 bars:

So, what are the characteristics of this particular flow?

1. The grammatical phrases, here indicated by puncutations at the end of sentences (“Tell me me who’s the freshest of them all? / I step inside the closet and that shit look like a loft. / etc.”), all abide largely by the barline. They are mostly 4 beats long, (“Tell tell tell me who the freshest of them all?”) with some smaller 2 beat phrases right next to each other that together add up to 4 beats (“Tryna get what’s in my closet, nah, bitch I bought it all” and “Yeah, bitch, I got it all”.)

2. Articulation: Big Sean says these words legato. That is, he mostly rolls them all together, with no unnatural separations between the words.

3. Rhymes: the rhymes are rather simple. They are made up of single words (“all” with “loft” with “balls” with “all”.) Furthermore, they are end rhymes; they occur at the end of the grammatical phrases. Next, they also all occur in the same place: right on beat 3. His rate of accent is low, at about 1 accent (again, roughly equivalent to “rhyme” here) per bar, being a throwback to the styles of the Golden Age of Rap.

4. Use of musical phrases: a musical phrase is a short musical idea repeated over and over, sometimes with small variations. There might be a musical phrase her: “Tell tell tell me who the freshest of them all” is so similar in rhythm to “I step inside my closet and that shit look like a loft” I am somewhat tempted to call it a musical phrase consistent of a beat 1 full of 4 sixteenth notes, a beat 2 full of 4 sixteenths notes, a dotted eighth note on beat 3 plus 1 sixteenth note, and then a beat 4 of sixteenth notes. Big Sean, in fact, is fond of the use of musical phrases, almost and perhaps past the point of becoming tedious. (For a discussion of musical phrases, see my Eminem “Business” analysis or my “Upping The Ante” postpost.) But here, I’d decline to make it a phrase, simply because the rhythms of it are so ubiquitous: you can find single beats all filled with 4 sixteenth notes all over rap.

5.) In terms of rhythm, as just described in the previous, Big Sean does not use a lot of syncopation; that is, there are no heavy metrical accents that occur off the beat. All off-the-beat notes are simply pick-ups to an on the beat accent, such as the word “I” in “I step inside…”, or “Tryna” before “claim what’s in my closet.” He is also fond of filling up a beat completely with 16th notes. You can see this in the music from “My Closet” below:

This is perhaps what delineates and separate’s Big Sean’s unique flow here so much from other rappers: his lack of strong syncopation. As a relatively small comparison, early Lil Wayne and Eminem use heavy syncopation. Practically all rappers rely on heavy syncopation; that’s what makes a lot of rap sound so aggressive, even when its lyrical content isn’t aggressive (such as Wiz Khalifa’s extremely, extremely awkward collaboration with Maroon 5 for their new song “Payphone.” If Adam Levine is singing about a lost love, why is Wiz Khalifa yelling at me about balling or whatever? That song in itself deserves its own analysis…a decidedly negative one, but one from which we could learn a lot.) This makes Big Sean flow sound like it has a lot of swag, pride, or whatever you want to call it: it makes the flow sound kind of lazy and laidback, but when you combine it with his words, it sounds pretty cool.

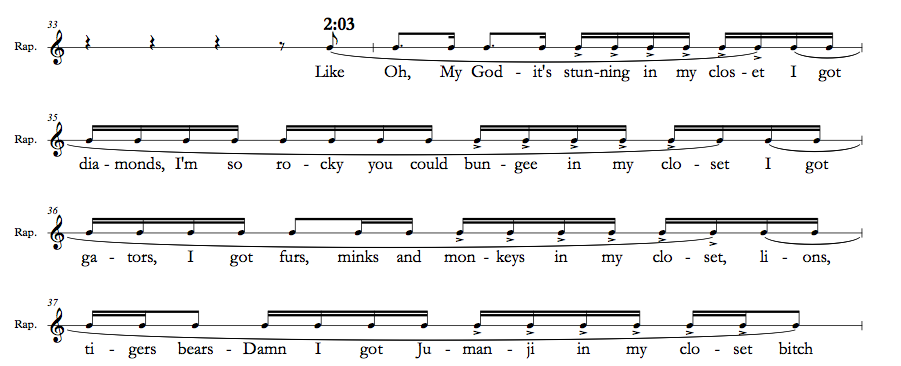

Big Sean brings this flow back later in the song, at 2:03.

This example hits all of our bulletpoints from before:

1. Grammatical phrases that abide by the bar line and are 4 beats long (“Like Oh, My God, it’s stunning in my closet”, “I got diamonds, I’m so rocky you could bungee in my closet”, and so on.)

2. End rhymes with a small number of syllables – here, the number is generally 2. (Although I’ve accented the words “in my closet” as well, since they are repeated so often here and throughout the song. In reality, though, repeating a word isn’t really a rhyme, so I still call them 2 syllable rhymes. I also call them end rhymes, because the rhymes are still at the end of rhymes, and the words “in my closet” almost count as their own grammatical separators with their great amount of repetition, like a period or comma.) End rhymes at the end of grammatical phrases. Rhymes that occur in the same place in the bar: here, again on beat 3, which is also characteristic of this flow.

3. Lack of syncopation – strong on-the-beat rhythms, with beats often full of 4 16th notes.

4. Legato articulation.

So, the flows are extremely similar, and easily identifiable as similar by the ear.

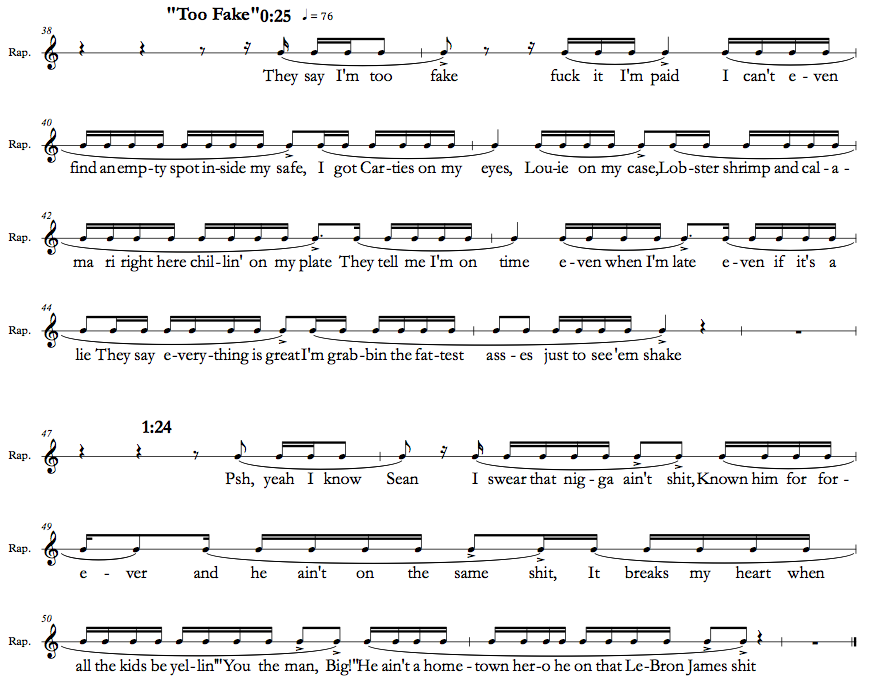

But can we find this flow in other songs? I think we can: check out “Too Fake”:

Consider the above example from “Too Fake”, at 0:25. Look familiar? Grammatical phrases abiding by the bar line, isosyllabic end rhymes, lack of syncopation, legato articulation – it’s all there. I consider that to be perfectly clear.

What about at 1:24 though? Here, Sean mixes it up a little. We see that there are still the isosyllabic end rhymes, syntactical phrases abiding by the bar line, lack of syncopation, and legato articulation. However, the accents are varied. Instead of just a strong, on-the-beat rhyme on (once again) beat 3, the rhyme is 2 eighth notes on beat 3 (“ain’t shit”, “same shit”, “man, Big!”, “James shit.) However, this preserves the lack of syncopation of the other archetypal examples, so I just consider them variations of the same flow.

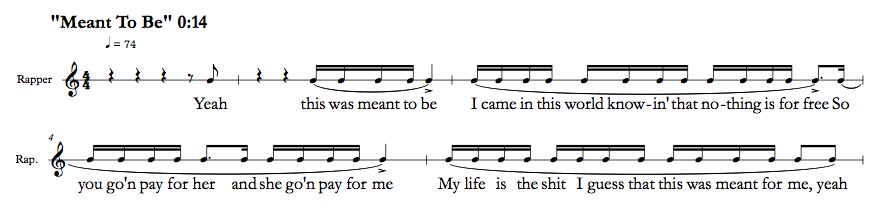

Another singular example of this flow is from “Meant To Be”, at 0:14 – it’s the chorus.

Look for the same 4 points on your own: grammatical phrases, indicated by the curved lines underneath the notes (such as from “This” to “Be” in the above example) falling within the bar line, lack of syncopation, simple end rhymes always falling in the same place metrically, legato articulation.

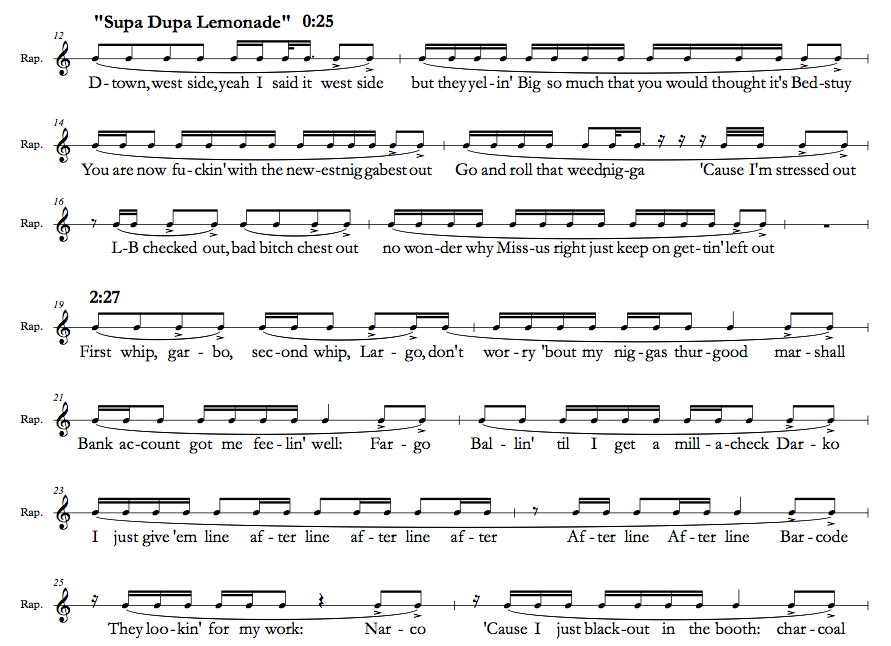

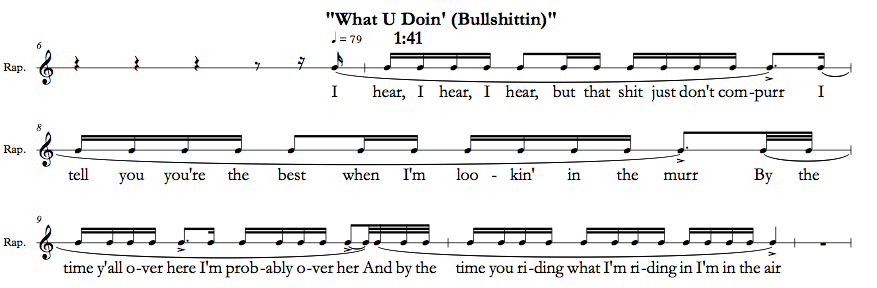

To avoid redundancy, here are more examples, just without the obvious explanation. However, it should be noted that these examples vary things a bit more, with less lack of syncopation and more extended rhythms, such as with 32nd notes in “What U Doin (Bullshittin)” and “”Supa Dupa Lemonade”:

So, we have established that Big Sean indeed does have a signature flow that he brings back again and again. In fact, this flow can be found all over the album, not just on these songs. But what are we to make of it?

Well, we could say that it shows he lacks creativity, and doesn’t quite cut it as a rapper. It could come across as repetive, and simply a crutch for him to lean on when he runs out of new rhythms to rap off of.

Instead, I would view this phenomenon as a positive thing. I think it’s pretty amazing that Sean has identified a flow with very unique yet consistent characteristics that stands out so much from not only the flows of his other raps, but also the flows of other rappers. It is almost instantly identifiable. Also, it fits his rapper persona extremely well: upper-class swag, still bad-ass, just not really gansta… not gonna talk about how many guns he’s got or drugs he’s sold or whatever, but still a BAMF. It is extremely hard to do this, to 1. Make it stand out from all other flows, but also to 2. Make it not get boring or tiring – to his credit, as we saw, Big Sean does vary this flow while always retaining its core identifying characteristics.

As mentioned briefly before, I’m hard-pressed to find another example of this in the rap repertoire. Perhaps we can make general statements about rapper’s flows, like “Eminem favors internal rhymes”, but we can’t identify a single flow. Furthermore, we might be able to identify what I’d call unique musical signifiers, such as the role of sextuplets in Outkast’s flows (Big Boi AND Andre 3000, as I explain here), but they are also easily co-optable by other rappers, and in fact are used by other rappers. It would be really cool to see other rappers try to do this.

So, we’ve identified what kind of rapper Big Sean is: not overly technically complicated, favors simple end rhymes with grammatical phrases that largely abide by the bar line. Remind you of any other rappers?

Perhaps a rapper who, in his words, has “blessed” Sean?

Perhaps the founder of the record label Big Sean’s on?

Yes, Kanye West and Big Sean are rather similar rappers, for the characteristics just described. They both won’t overwhelm you technically, but they will go for the knockout verbal play: the double entendre, the pun, etc. How similar is “Don’t worry ‘bout my niggas, thurgood – Marshall / Ballin’, til I get a mill-a-check, Darko” similar to “’Oh My God, is that a black card?’ / I turned around and replied, why yes / but I prefer the term ‘African-American express.’”, a gem from Kanye’s debut album?

And don’t worry, I’ve also analyzed Kanye’s music too, including his raps here, as well as his song structures on “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy” here, and his production for the song “Monster” in this article here, too. And, if you want something a little more technical, feel free to check out the polyrhythms I talk about in my Nas article here.

Hope you enjoyed it! Check out my other posts, and follow me @ComposersCorner on Twitter. Also, I’m still teaching people how to rap and produce, so check it out! Also, I’ll be putting up one of my songs finally on here, so look for that! Thanks for reading this rap music analysis!

You should check out Kanye's 1st 4 albums and a lot of tracks off of MBDTF if you don't think he can be technical in rhyme schemes.

Chicago and other Midwestern city emcees, also often have a different approach from others in the West, East and South.

Wow. This is hecka informative and thorough. It would be sick if you did an analysis of Logic's varying flows and lyricism

Thanks for the compliment man! And yeah, I'd be happy to do an analysis of Logic's flow. Just email me at [email protected], telling me your favorite song of his, and I'll take a look.

Thanks again man!

Peace!

-Martin